SX70 shutter (updated)

I have expressed my doubts about what is the actual aperture of the SX70 camera and about the outrageous claims about shutter speeds of 1/2000 (or, for that matter anything faster that 1/180th of a second or aproximately 5,6ms). But even then, watching those ‘impossible’ pictures at 1/2000 and 1/1000 something was odd. What is happening? Keep reading if you want to find out.

Having had the inmense luck of been able to discuss the matter with the person who first really understood it Dr. William T. Plummer (pinch me, no, really I mean it, he and all the Polaroid ‘oldtimers’ that I have contacted are very nice people, but singularly Mr. Plummer) he has a vast body of papers and some of them are SX70 and Polaroid related.

Dr. Plummer derived a design that could make this kind of shutter even better:

During the first third of the total time the shutter opens with its area increasing linearly, then for the second third the shutter holds its area constant, and during the third third the closing is again linear with area.

Part of this study was Monte Carlo, with thousands of possible trajectory shapes. Take a look at pages 19-24 in my paper BEYOND RAYTRACING, where that trajectory is compared with several others

I find this paper fascinanting, and only wish I could understand it better, actually this phrase in BEYOND RAYTRACING says it all:

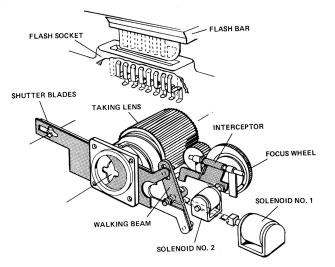

In one convenient design, used in most Polaroid cameras since 1972, the photographic shutter operates by opening and closing the optical path at the aperture stop of the system, so that one mechanism is both shutter and iris.

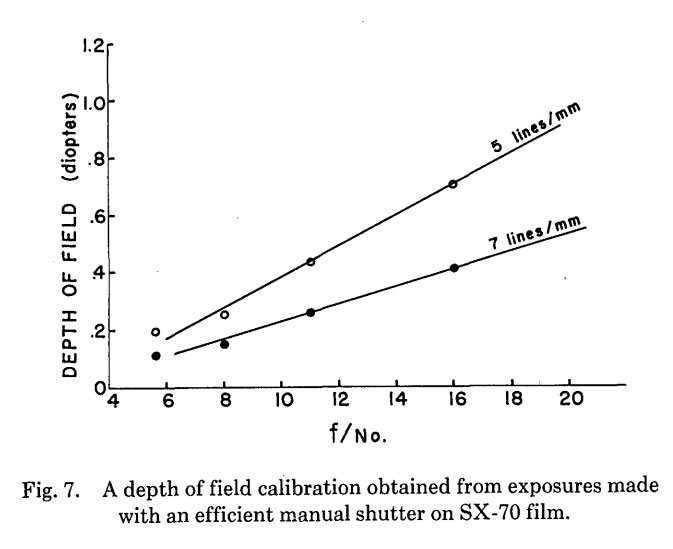

Any given exposure is thus the accumulation of light from a progression of aperture sizes.

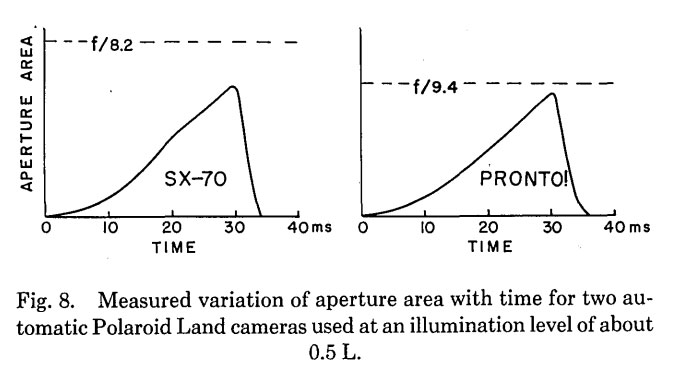

So the answer is that there is no “aperture” for a given shot on the SX70. We might be able to find or estimate the EV value. We can pretend that the aperture is f./8, but that is only the maximum aperture possible. It is clearly visible in this graphic.

By luck on the Edwin H. Land Essays page 218, volume I (highly recommended) found some answer to the question:

The text says: As the shutter is opened, the aperture changes from f/96 to f/8 in 25 ms. Brightness levels less than 50 cd/ft^2 cause the aperture to open to f/8, the maximum opening.

But the plot thickens, as the consequences of this inefficient shutter design have positive repercusions on the quality of the picture!

If we go back to Dr. Plummers paper Beyond Raytracing there is a section called The photographic shutter as a “lens elemment”

I am not going to pretend that I understand all of it. But I understand the gist of it.

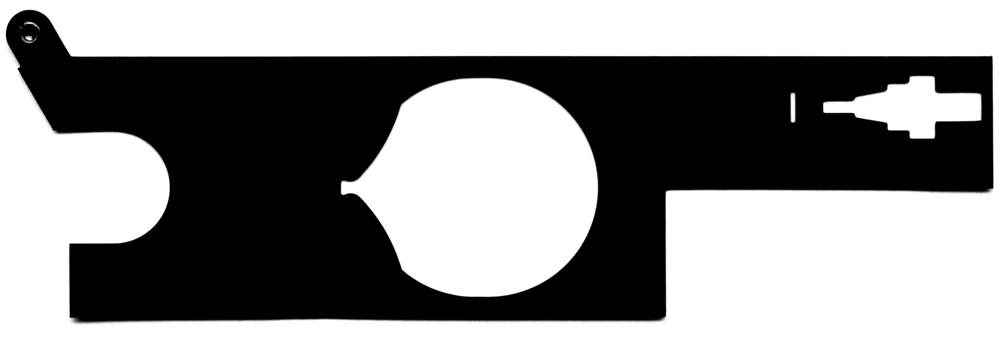

First the “teardrop” shaped of the shutter blades is not (by far) random, it has been carefully chosen for its purpose:

COMMENTS BY DR. PLUMMER:

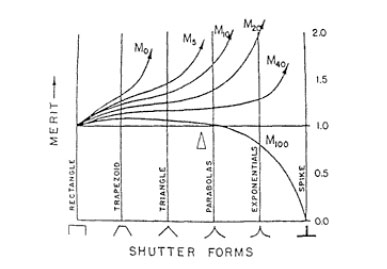

This improvement is shown in the graph you present without comment a little later, just before your shutter blade scans. The merit function from my paper is graphed agains a series of shutter curves of diminishing efficiency, showing how the merit judged at different spatial frequencies changes with those curves. Every merit curve is improved with the trapezoidal choice. The merit for higher spatial frequencies keeps improving toward the right. The little triangle is where the Polaroid shutters fall; down a little from optimum for the lowest frequencies, M100, but no worse than the efficient shutter would give, and distinctly better for higher spatial frequencies. This actual shutter is pretty good, and I wouldn’t change it.

I used this merit function approach to evaluate the shutter trajectory shapes in a way that was separate from the independent tradeoff between aperture size and time. Every one of those shapes can be made wider and lower, or narrower and higher, but the merit function will still rank them for performance.

Another story: I don’t know about the later SX-70s, but in the early ones the two shutter blades were made of different materials, Mylar and stainless steel. That was done to balance them. The solenoid and beam mechanical design would otherwise change speed a little when the camera was tilted sideways, and the greater weight of the steel blade avoided the problem.

Here is my high quality scan of the shutter-blades/iris of the SX70.

But the amazing part is this, (in Dr. Plummer own words) is:

In an image that is static and in sharp focus the result is not remarkable, but in the presence of focus errors and motion smear the result can be quite interesting. One surprising conclusion is that the photograph, in the presence of both defocus and motion, may be substantially better for the use of this form of shutter, rather than the very common focal plane shutter.

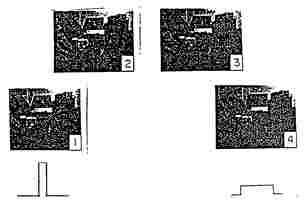

Unfortunately the ilustrations for the experiment are of low quality, but we can see the process:

Here first are a set of four photographs taken of a table-top scene. There is a moving calendar in the background, in sharp focus, and a variety of cups and bottles closer to the camera. From left to right the manual camera shutter was varied from a short exposure at f/8 to one four times as long at f/16. There is a progressive improvement in depth-of-field and a progressive worsening of the motion blur:

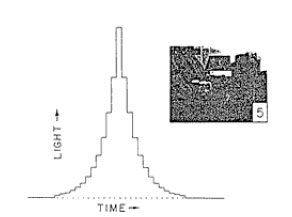

The interesting exponential shutter function can be simulated with a manual conventional shutter by taking a multiple exposure. The next illustration shows the same scene photographed with the exponential shutter function, simulated with a set of 25 exposures, advancing from f/64 to f/8 and back again, as graphed:

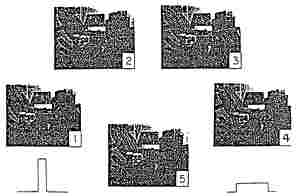

We can use the resulting “exponential” picture, #5, for an easy experimental comparison with the basic rectangular shutter. Here we see all of the pictures in a group. These may be a little hard to see on the screen (and utterly impossible in a small reproduction), but when viewed under normal conditions picture #5 is a good match for #l in its ability to freeze motion, is a good match for #3 in depth of field, and is superior to #2 by both metrics:

In fact, the observed “exponential shutter” result is superior in both motion-freezing and depth of field to any single pair of aperture and time settings on the manual shutter. Once again we have found an example in which an image sharpness issue can be understood only by following the illumination.

That means that the teardrop shape of the blades of the shutter, plus the way it operates when taking a picture, and the fact that there is no aperture, has beneficial consequences for the photographer, compared to a “normal” plane shutter. Concepts like aperture, and shutter speed are no longer clear-cut and get a new meaning, hard to explain, and of ‘infinite’ possibilities: yes that is probably yet another reason why we love the SX70!

Here again in Dr. Plummer words:

The shutter efficiency issue was related. At the time I proved that our less “efficient” shutter was superior, the manager of the electronic program had been embarrassed by the “inefficiency” of his shutter, and was working hard to find a way to make it “efficient”. My result saved us that need. When Kodak came out with their infringing instant product a few years later, they used an “efficient” shutter, selecting one of two apertures for the exposure and holding it fixed. Comparison photographs nicely showed that our “inefficient” shutter was superior. It also cost us less to make

Finally If you want to know more about SX70 and the amazing people that designed it I recommend this video of a talk by Dr. William T. Plummer:

You have the slides here

Comments