How Polaroid bet its future on the SX-70

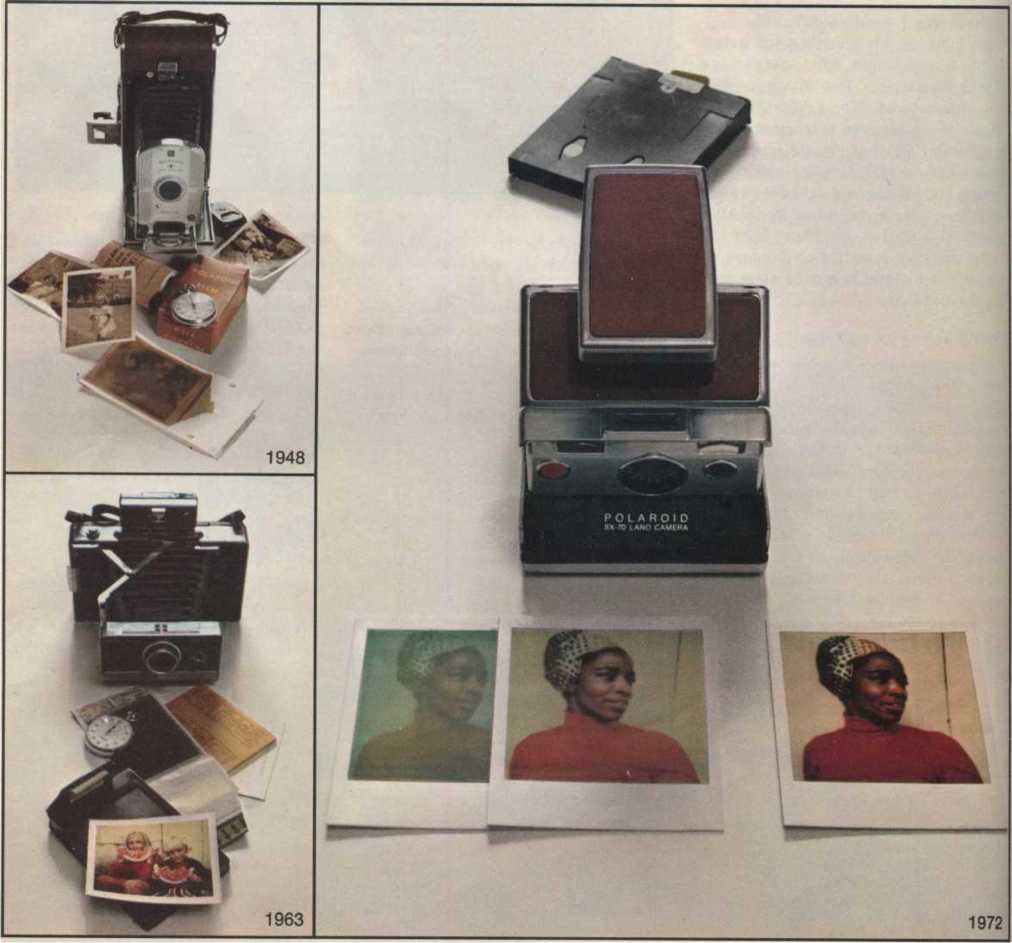

The earliest ancestor of the SX-70 weighed five pounds and took only sepia pictures with big, inconvenient rolls of film (upper left). The Color Pack series (lower left) introduced handier packs of film and produced both black- and-white and color photos. But the user still had to time development of the film, then peel it apart and dispose of a messy negative. The twenty-four-ounce SX-70 automatically ejects a plastic-sealed color picture that develops while the photographer watches.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER NOTICE this is an article from the January 1974 issue of Fortune Magazine, written by Dan Cordtz, with Aimee Morner as research associate. I find it a fascinating read, and very very hard to find. I have not found how to purchase the article on line unlike other SX70-related articles that I would never publish. Finally I found a print copy, but they would not ship to EU, so I had to have it sent to a friend in Brooklyn. Early on he noticed that it had a missing page. I tried to locate another print magazine, but nothing reasonable came up. So I finally got the page (kid-you-not) by means of laboriously extracting the images out of Google Books snippets. I have patiently transcribed the text. So the bottomline is that I don’t know if the article is under copyright protection. If you think it is infringing your copyright please contact me and will remove the article inmediately.

Reading this article in the future makes you think in what SX70 means, and what an accomplishment it was. Dr. Land risk everything on his secret SX70 project by assuming that he could accomplish a truckload of breakthroughs.

January 1974, by Dan Cordtz

A great technical achievement awaits its ultimate test in the marketplace.

“Optimism is a moral duty” said Edwin H. Land recently. The sixty-four- year-old inventor-industrialist made that remark in a specific context: the obligation of the world’s affluent minority to try to improve the lives of the disadvantaged. Land would certainly not suggest that business executives have a moral duty to risk their shareholders’ funds on mere faith that everything will turn out for the best. Nevertheless, as founder, chairman, president, and research director of Polaroid Corp., he has demonstrated over a quarter century the sort of boldness in business that anyone else might well regard as the wildest sort of optimism.

Today, Land and Polaroid are approaching the denouement of the biggest gamble ever made on a consumer product: the eight-year program to bring out the SX-70 camera and film. Although the company has never officially revealed the project’s cost, Land referred to the SX-70 in a recent interview as “a half-billion-dollar investment.” And one of his top associates remarked privately that the total cost is even higher than that.

The returns on this breathtaking venture are not yet in, of course. In recent months some members of the investment community—including institutions whose earlier euphoria had helped drive Polaroid stock as high as 143% a share last June—have voiced public fears that profits would be a long time in coming and then may not be as great as expected. Early last month the price of the stock had fallen below 70.

Out of current earnings

Although Land and his family, with 4.9 million shares, have been by far the biggest losers from the stock’s decline, he has no real interest in the size of his personal fortune. He is conscious of the impact on his executives’ options, but mostly he feels that attention focused on future earnings “is a distraction from concern with what we are doing.”

Normally a gentle, soft-spoken man, Land gets really passionate when it is suggested that his own ebullience may have misled the security analysts in the past. “I take violent exception to that!” he declares heatedly. “I agree that their disappointments come from exaggerated expectations. But they’re theirs.” Moreover, he points out, Polaroid’s large expenditures have bought physical assets “three times as valuable as when they were created,” and give the company a unique capability to make the next generation of cameras. “Our assets are priceless,” he asserts, “because we’re the only ones who can bring them [the new cameras] into being.” Except for $100 million raised by the sale of stock in 1969, Polaroid financed the entire SX-70 project from current earnings. Last year the company had estimated profits of $55 million; earnings reached a peak of $71 million in 1969.

Certainly there is no obvious reason to feel more skeptical of Polaroid’s outlook today than there was back in 1972, when the analysts were so enthusiastic. On the contrary, since then the company has demonstrated that it can turn out both a fantastic chemical product—the film—and the complex, electronically controlled camera to use it. Production difficulties remain, and they are not trivial. Current output, averaging 5,000 cameras a day, is only half of what Land had hoped for by this time, and the national introduction was nine months behind schedule.

The delay stems in part from the fact that Polaroid, which previously relied on outsiders to make its cameras and the negatives for its film, moved for the first time into large-scale manufacturing and assembly in 1972 with the SX-70 system, and it is still struggling up the learning curve in its new plants. The company must improve the reliability and yield of its output, while it is simultaneously increasing its volume. As it does both, costs will fall, and profits could soar. Polaroid officials have publicly stated that they expect to pass the break-even point on both cameras and film early this year.

What about Kodak?

Even assuming complete success in increasing production and cutting costs, of course, Polaroid’s profits will depend on two closely related imponderables: the size of the market for SX-70 cameras and film, and Eastman Kodak’s long- awaited decision on whether to enter the instant-picture market.

Polaroid has never made its sales goals public, but some officials talk privately about selling six million SX-70 cameras as a conservative objective for the next few years. The more exuberant of them foresee an ultimate market more than twice that big. For an idea of how ambitious such plans are, consider this: The SX-70 carries a suggested retail price of $180. But in 1972, according to the authoritative Wolfman Report, U.S. sales of all cameras priced above $100 totaled only 1.3 million.

On the other hand, there never has been a camera anything like the SX-70.

It is an enormous advance over Polaroid’s earlier products—and the company has sold nearly 40 million cameras and the film for nine billion pictures since 1948. When Land introduced his first camera, only a handful of observers outside the company anticipated the demand. The potential market for the SX-70 may be just as surprising. The photography buff responds strongly to innovation. Kodak’s phenomenal success with its Instamatic series (which ranges in list price from $11 to $225) is a good illustration of the attraction of something new.

Difficult as it is to assess the market now, it is even harder to predict what direct competition from Kodak could do to the SX-70. Kodak, not surprisingly, declines to discuss its future plans. But Polaroid’s officers, almost to a man, say that they expect their big rival to get into the instant-picture business sooner or later, and probably within the next couple of years. Almost certainly, such a move would take away some sales from the SX-70. But there are good reasons to believe that it would not destroy the smaller competitor.

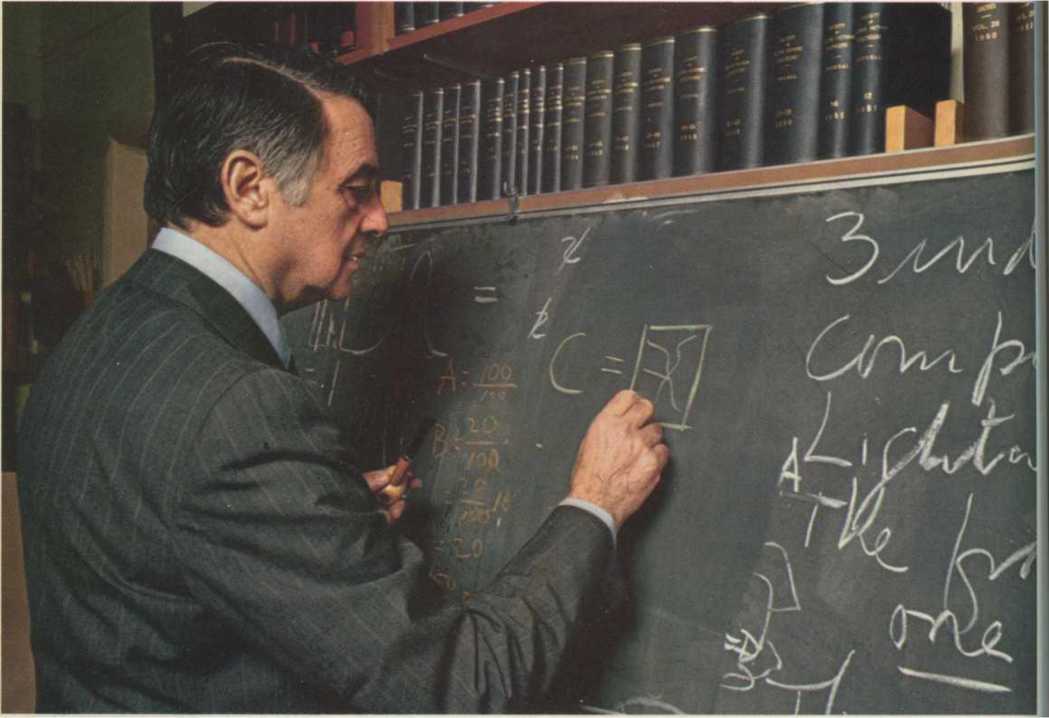

Ever the scientist, Edwin H. Land works out still another equation in his book-cluttered office. He was only seventeen, and a freshman at Harvard, when he began work on a process for making light-polarizing filter material in plastic sheets. Leaving Harvard to exploit this discovery, he never did get his degree. But Land has never stopped studying and inventing.

Kodak, in spite of its impressive technical competence, will have to struggle over most of the same obstacles that Polaroid encountered as it pioneered instant photography. It must also contend with the formidable wall of patents that Polaroid has erected around its products. And it is not likely that Kodak would launch an all-out assault. Instant pictures will never be more than a minor portion of its huge business. And the last thing Kodak would want is to attract the attention of the Justice Department by taking over that market and crushing relatively tiny Polaroid.

The memorable moments

However the venture turns out commercially, the mere production of the SX-70 must already be counted as one of the most remarkable accomplishments in industrial history. The project involved a series of scientific discoveries, inventions, and technological innovations in fields as disparate as chemistry, optics, and electronics. Failure to solve any one of a dozen major problems would have doomed the SX-70. Still, Land remembers the most exciting moments as those when people perceived the way things might be done, rather than the later times when they actually were done. The difference in pleasure, he explains with a smile, is like that between “conceiving a child and having to bring the damn kid up.”

The new system is very close to the ideal that was in Land’s mind thirty years ago, when he first set out to invent what he calls “absolute one-step photography.” The term means that the photographer need do nothing more than compose and shoot a picture that becomes available while he still has his subject before him. As anyone not totally insulated from advertising must now know, the SX-70 requires only that its user compose his picture through a viewfinder, focus it, and press a button. The camera’s electronic computer sets the shutter speed and aperture. The picture is instantly ejected from the camera and develops itself in front of the photographer’s eyes. There is nothing to peel off or throw away. The photo is sturdy, plastic-coated, and can be stuck in a pocket or purse at once.

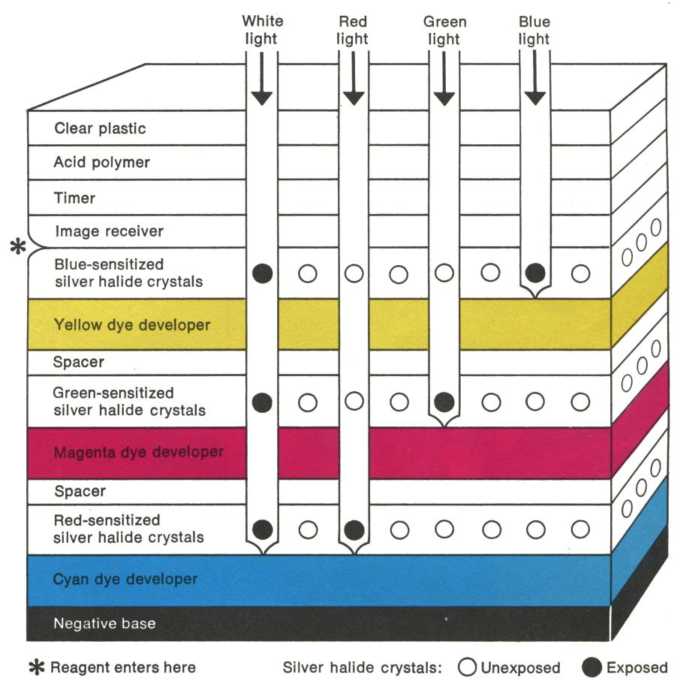

Much thinner than the hyphen in SX-70, each sheet of the camera’s film is a sandwich made up of eleven layers of chemicals. The negative has three sections, each with an emulsion layer of silver halide grains sensitized to one of the three primary colors (blue, green, and red) and an adjacent layer of metallized dye developer (yellow, magenta, and cyan, complements of the primary colors). Blue light hitting the film exposes the blue-sensitive silver halide and creates a trap for the yellow dye. The same process takes place as light hits the green and red emulsion layers. As the exposed film is ejected, steel rollers rupture a pod of reagent and spread it between the negative and the positive. The reagent includes an opacifier that excludes light while development takes place, then turns clear to show the emerging picture. Alkali in the reagent dissolves the dye developers, which migrate toward the image-receiving layer. If the dye developer encounters exposed grains of silver halide as it passes through its adjacent emulsion layer, some or all of the dye is immobilized. Where blue light has struck the film, yellow dye is trapped in the blue-sensitive layer, while magenta and cyan get through. They combine to form blue in the image-receiving layer.

In the early 1960’s, Land spelled out a long list of goals for the new system. He wanted to produce a competitively priced film that did not demand the photographer’s time and attention, and left nothing to throw away. This film would be used in a small camera that was simple to operate but had a wide range of capabilities. “In retrospect,” says Richard Wareham, vice president of the engineering division, “it looks easy. But then it was like trying to run a car without gasoline.” The difficulties were dismayingly evident, and some of the technical staff doubted the feasibility of the idea. But when Land feels strongly about a project, he can and will force it through. Besides, remarks William J. McCune Jr., executive vice president and a close associate for thirty-four years, “one thing about Land—when he is doing something wild and risky, he is careful to insulate himself from anyone who’s critical. It’s very easy in the early stages to have a dream exploded.”

Dyes that live forever

The starting point was the film. Since no garbage was to be left, the negative and the final picture had to be contained in the same package. The dyes that form the image would have to survive in a hostile environment of sealed-in chemicals and moisture. This made it even more difficult to achieve another objective: dyes with unprecedented resistance to fading. Howard G. Rogers, vice president and senior research fellow, a Land collaborator since before Polaroid was founded, had previously developed a molecule that combined dye and developer for Polacolor film. In 1965, with five research chemists, he set out to incorporate a metal ion in the dye portion of the dye developer.

Such metallized dyes were known for their permanence. Sheldon A. Buckler, vice president of research, declares that the SX-70 dyes have “more stability than any others used in photography. We left photos for two months under light fifty times more powerful than standard fluorescent light, and they haven’t altered significantly.” But early experiments with the use of metallized dyes in photography, Rogers admits, “were pretty horrible.” And not until early 1970 was the last of the three required dyes—the yellow one—successfully produced. (The others were magenta and cyan.) By that time, the company had already spent some $130 million on new manufacturing facilities to make products for which the yellow dye was an essential component.

Metallized dyes also make possible more brilliant and saturated colors than Polaroid film had ever had before. But they are sluggish in their reaction, and move more slowly through the micro- scopic layers that make up the film (see the diagram). This meant that the total development time would be longer than that of previous Polaroid color film, and reinforced Land’s determination to have the picture take form outside the camera.

But photographic film cannot truly develop in ordinary light, which is a billion times brighter than the light that passes through a camera lens to register an image on the film. As the SX-70 film emerged, the negative—where the chemical synthesis of dyes takes place—would have to remain in total darkness. What Polaroid needed was a compound twice as opaque as a filter used for viewing an eclipse of the sun—but one that would turn completely transparent after development so that the picture could be seen.

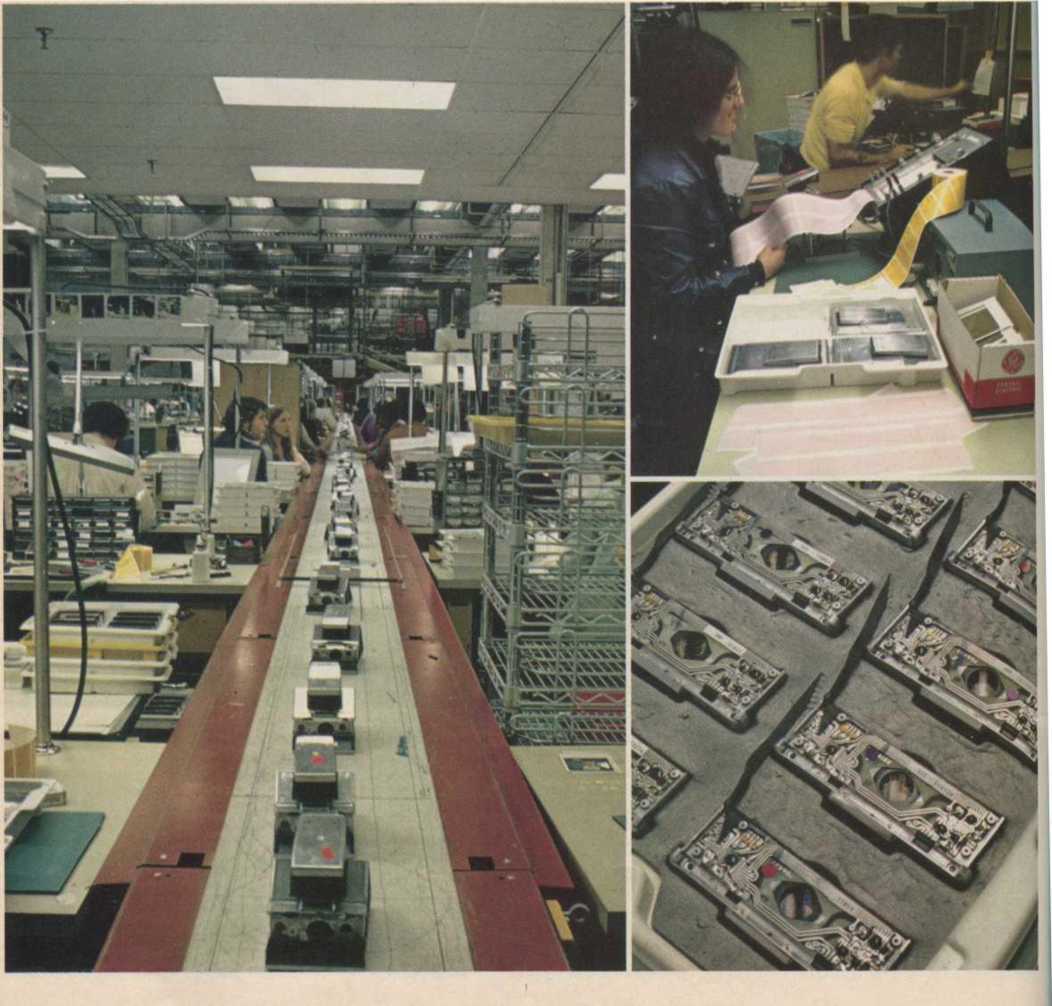

Finished SX-70 cameras move along the final assembly line (left) at Polaroid’s $25-million camera plant in Norwood, Massachusetts. The facility’s testing equipment, such as the device (upper right) that checks the power consumption of each camera, incorporates the most advanced technology. Thirty-three tests are made on the miniaturized shutter unit —the heart of the SX-70 (lower right).

“The way the camera was defined,” noted Buckler, “something like that had to exist. But the problem was, not just that it didn’t yet exist, but that we didn’t even know the phenomenon that would give it the foundation to come into existence.” It was “the toughest job I’ve been involved with in my life”—and he added, with studied understatement: “There were some doubts.” The search for such a shielding substance began in 1967, and a major program, with eighteen laboratory chemists at work, was under way by the following year. The problems were staggering. “We had literally three dozen schemes for doing it,” Buckler says. The first job was to discover any way to do it, and the second job was to find a practical way to do it.

The missing clue

Stanley M. Bloom, assistant vice president and director of the project, carefully points out that “you never start with nothing. We knew that some materials color in alkali [the medium in which development takes place]. The clues were in the scientific literature—we had to build on them. But one thing wasn’t in the literature: we had to find a material that would totally switch itself off. It’s easy to find a substance that will decolorize in acid, but we wanted it to have color in a high alkali content, then turn transparent when the alkalinity dropped just a little.” Literally hundreds of chemicals were formulated, tried, and discarded before the first tiny quantity of the right one was produced.

On November 4, 1969, in the dingy, hundred-year-old red-brick Cambridge building where Land has his working office, this opacifier was successfully demonstrated for the first time. It was an emotion-charged scene, with fifty of the company’s top scientists crowding into the color laboratory. As the exposed film, under the direct rays of two sun guns (equal to sunlight at the top of Mount Everest), began to clarify, excitement mounted. And when it became obvious that the color negative had developed, a great cheer went up, backs were slapped, and impromptu speeches were delivered.

Twenty-nine months later, when the first eighty pounds of opacifier were actually manufactured, the achievement was marked ceremonially. A triumphant Land had ordered a cake on whose frosted surface was written: “and the darkness shall become light….” The sentence, he recalls with a smile, “had a nice Biblical ring, even though it was written for the occasion.”

Going for independence

In the meantime, Polaroid had made a momentous technological decision: after years of depending on Kodak, it would make its own negatives for the SX-70. Only a handful of companies in the world have been commercially successful at making even conventional color film.

No less a company than DuPont tried and gave up. Moreover, the complex negative for the SX-70 film is more difficult to coat than that of any other color film. Polaroid had to figure everything out- for itself. Kodak, understandably, has never permitted Polaroid technicians to see its negative-coating plants and has declined to reveal any details of the process. Nevertheless, Polaroid began work in a small pilot plant in Waltham.

By early 1969 it was certain enough of success to commit $60 million to build a new plant in New Bedford to make negatives for the SX-70 film. The fantastically complicated factory—actually one giant machine that requires a surgically clean environment and uses prodigious quantities of purified air and water—has been a resounding success from its start-up in 1972. Usable negative was produced on the second run, and since then Polaroid has produced more than ten miles of wide negative sheet at a time.

Polaroid’s determination to make its negatives also required it to produce many of the exotic organic chemicals for coating the film. “The compounds posed special problems in manufacturing,” says Bloom. “We needed to control all of the materials closely. We needed a very responsible group. The smallest amount of impurity in the raw material could ruin a whole batch.” Hence, in 1969, another $13 million was poured into a chemical plant in Waltham.

An army of inspectors

The negative-manufacturing process is so delicate that when something goes wrong, it is seldom easy to figure out why. The analytical tools available are simply not up to the task, says I.M. Booth, the vice president in charge of negative production. Negative material is continuously being tested, and the biggest group of workers in the plant is the little army of people involved in inspection.

The plant itself, with its chemical vats, miles of pipes, and multistory confusion of press like rollers webbed with film, is controlled largely by computers.

Oddly enough, the most troublesome part of SX-70 film production is the assembly and packaging of the final product—a job that Polaroid has been doing routinely for years with its other film. The coated negative and positive sheets of the new film must be kept from light while they are bonded together and sealed to form a plastic sandwich only 9/10,000th of an inch thick.

Then ten of these laminations must be packed tightly in a small plastic case and covered with a lightproof piece of cardboard. “It is terribly difficult to assemble huge quantities in the dark,” explains McCune, the executive vice president, who has had overall responsibility for getting the manufacturing operation under way. “The question is not whether we can do it, but whether we can do it consistently and with high yields.” From the first, Land had been certain that his chemists could produce the film. So he immediately ordered design of the ideal camera to use (or, in the jargon of the industry, to “burn”) that film. His previous cameras, whatever their utility, were not aesthetically appealing. And as a practical businessman, Land knew that, because of their unwieldiness, Polaroid cameras tended to be retired to the closet shelf comparatively soon. A pleasing appearance and convenience were absolute requirements.

One allowable failure

The lower limits of the camera’s size were set by the dimensions of the smallest acceptable picture, and the largest more or less by the size of a man’s jacket pocket or a woman’s purse. Land carved a block of wood in the size he envisioned, stuck a small lens in one side and covered the block with tan vinyl. For months this was the physical model.

Initially, he did not want the camera to open up or fold. The intractable laws of optics, however, demand a certain distance between lens and film (focal length) to produce a picture as big as Land had in mind. This meant that the image would have to be bounced back and forth inside the camera by an involved series of mirrors.

Wareham and his crew tried for a long time to come up with an acceptable arrangement. Finally, he recalls with a grin, Land told him: “You’re allowed one engineering failure and you’ve just had it.” Attention turned to a design that required only one mirror to achieve the four-and-a-half-inch focal length required. This dictated that the camera, when in use, would have what Wareham calls “the funny shape we have now.” Land also insisted that the new camera be more than a simple snapshot device. He wanted a wide range of focusing possibilities. Yet the lens had to fit inside a folding shutter unit. After months of effort, designers came up with a remarkable four-element lens. Only the front element moves—less than a quarter of an inch. Yet the camera can focus on objects as close as 10.2 inches away—five inches with the attachment of an inexpensive additional lens. (A standard Instamatic will focus no closer than three feet, and neither will most 35-mm. cameras without costly special lenses.)

The SX-70’s extraordinary range demanded a viewfinder of unusual accuracy. “Our early attempts were odd outgrowths, like telescopes,” Wareham says. “We failed miserably. Eventually we thought we’d have to give up the folding body, and we even designed some rigid models that looked like the SX-70 when it’s open. We worked into 1970. Finally, Land said: ‘Forget it. Keep your heads down on the camera. I’ll invent the viewfinder.’ That was a good deal, so we grabbed it.”

What Land conceived was a significant improvement, but brought new problems with it. He decided to make the SX-70 a single-lens reflex (SLR) camera: one in which the image is viewed through the same lens that takes the picture. This makes for great accuracy in composition and is the type preferred by most serious photographers. But SLR cameras also require a means of getting the image from the lens to the photographer’s eye.

“Every trick we could think of”

Most SLR cameras have one mirror to reflect the image from the lens upward to a prism and thence to the eyepiece. But the SX-70’s thin, folding design, as well as the size of its film, ruled out a prism—there was not enough room for it. The whole job had to be done with mirrors.

And according to Richard Weeks, director of optical engineering, “It has taken virtually every optical trick we could think of.”

Transmitting an accurate image through the camera lens to the photographer’s eye required three mirrors and two tiny lenses. The concept was not so difficult. The execution was nearly impossible. “Almost every part was an invention,” says Weeks.

The first essential was a Fresnel mirror—a flat mirror that reflects light like a concave mirror because of microscopic grooves in its surface. Fresnel mirrors are nothing new, but in the past they had always been made by rotating the mirror around its center while a diamond tool cut the surface. Polaroid needed a mirror whose focal center did not coincide with its dimensional center. Ultimately, the engineers found a way to wobble the diamond cutting needle with the precision required to produce the off- center mirrors.

The other optical components presented even greater difficulties. Three of them (a concave mirror and two lenses) were aspherical, which meant that they would be not only extremely hard to produce but almost impossible to measure precisely and thus to reproduce with the required accuracy of 20/1,000,000th of an inch. Polaroid’s scientists had to invent an entirely new machine to measure aspherical surfaces. “Before we knew that we could measure them, we couldn’t be sure that we could make them,” Weeks explains. “And until we knew that we could make them, there was no point in designing them.”

It took four men two years to produce the measuring machine. Delicately balanced on hydrostatic bearings, it uses a laser to measure the dies (from which the lens molds are made) to tolerances of millionths of an inch.

Designing the optical system pushed computer capability to its limit. “We had to develop whole new design routines,” explains William Plummer, a key member of the research team. “The computer might ordinarily use thirty numbers. In this case there were twenty-five variables in the eyepiece alone, another twelve in the wafer lens, and twelve more in the mirror.”

Impossible electronics

Some of the camera requirements were set by limitations of the film, which does not forgive inaccuracy in exposure. The user of Kodak film sends it to be developed in a laboratory where even fairly serious exposure errors can be corrected in the processing, but since Polaroid film is self-developing, no such expert outside assistance is available. Hence the camera had to have a sophisticated system to calculate and control exposure.

Previous Polaroid cameras had shutters whose speed was controlled electronically. But the SX-70 was to have both shutter speed and aperture controlled automatically. The designers wanted shutter speeds accurate to plus or minus 10 percent, compared with an average of 25 percent for even good 35-mm cameras. This need for precision dictated a unique electronics system.

Polaroid turned to Texas Instruments, with which it had principal supplier it also assigned a portion of its requirements to Fairchild Camera & Instrument. Neither company was sure that the camera- control circuitry—with six miniaturized computer chips containing the equivalent of some 325 transistors—could be made at the target prices. Their fears were well founded. Until recently, the electronic modules posed the biggest obstacle to volume production of cameras. Eventually, Texas Instruments came up with a new design that has enabled it to increase production of the modules and cut their cost from $30 each to $6 Fairchild has not yet been able to get its costs down to that level.

All the action takes 1.5 seconds

Setting the shutter is only one of the electronic circuitry’s jobs. When a photographer touches the red button that operates the SX-70 camera, he sets off a complicated chain of actions. The shutter, which has been open to permit light to pass through the viewfinder, closes. The hinged fresnel mirror moves up, bringing another mirror into position to reflect light to the film. The shutter opens and closes to record the picture. If flash is used, its timing is synchronized with the shutter opening. Then, at the rear of the camera body, a tiny pick pulls the exposed film forward so that its leading edge is seized by a set of rollers. They pull the film through, rupturing the pod of reagent and spreading it evenly throughout the film sandwich, and the camera—as Land puts it—”hands you the picture.” The Fresnel mirror moves down again, the shutter opens, and the viewfinder is once again operative. Finally, a counter moves one notch to show how many pictures are left. All of this precisely timed and coordinated activity takes place in 1.5 seconds.

The electronics module directs the sequence which is carried out by a tiny, remarkably powerful, high-speed motor. When Land decided that the camera should be automatic, no satisfactory motor existed. Eventually the engineers adapted one from the motors used in children’s model racing cars.

Batteries from a printing press

Motors, of course, require power - much more than is needed to touch off flashbulbs. Land was determined not to increase the camera’s size (already growing alarmingly) by stuffing in a conventional set of batteries. He also wanted to relieve SX-70 owners of the nuisance of replacing batteries. The obvious but difficult solution was a battery in the film pack, to be thrown away after each set of ten pictures had been taken.

The battery had to furnish eleven short bursts of relatively high power (6 volts) at intervals of about 15 seconds, retain power over a broad temperature range (from freezing to 100º Fahrenheit), and —most difficult of all— fit into the film packs. In 1968. Polaroid took its idea to ESB Inc. of Philadelphia, which makes Ray-O-Vac batteries.

The electrochemistry of the new battery has been known for a century. But the design and packaging format are entirely new, as is the way in which the battery is made. The nineteen layers of materials race in large sheets through a series of machines. One, which coats zinc and manganese dioxide on plastic, closely resembles a printing press. At the end of the line, all of the layers are brought together and cut to size. Then the edges of the paper-thin, sheet-steel outer layers are sealed.

It’s a tricky business the chemicals that generate the electric current have to be coated onto the insulating material accurately and at high speed. The seals, of course must be perfect. And every, thing must be assembled to tolerances of a thousandth of an Inch.

Initially, difficulties with battery production were the despair of both ESR and Polaroid. Film assembly was held up by shortages and by unacceptable shipments. Worse, many of the batteries failed after the film parks were in the hands of customers. “I can’t think of anything more frustrating than getting out your last pack of film on an important occasion and discovering that the battery is dead.” says Buckler, who is currently engaged in a joint effort with ESB to improve reliability. For the present Polaroid is putting a final-sale date on the film that is only five months after shipment.

ESB already having nightmares with the new battery, was further embarrassed when Land, while taking pictures on vacation In New Mexico, used several packs of film that produced pictures with a bluish cast. This can happen if the film develops in extreme cold, but the New Mexico weather at that time was mild. Tests back in the labs in Cambridge revealed that gaseous effluvia from the batteries were affecting the film color. A special material) had to be coated in the battery surface to trap the gas.

A distressing variety of other troubles have cropped up with the batteries: pinholes in the plastic conductor material, a tendency of the steel outer covering to pull apart, electric shorts along the edges of the cut areas, and. especially, sealing failures that caused leaks. The coat of scrappage was sobering. If one of the batteries four cells is bad, of course, all are worthless ESB is now working in its lab on materials that could make the manufacturing process more reliable and bring its costs down sharply.

In any event, both Polaroid and ESB insist that batteries are no longer limiting the output of film packs.

A pitch by Lord Olivier

Even while still struggling with myriad production problems large and small. Polaroid fifteen months ago mounted a characteristically aggressive marketing program for the SX-70 Because of a shortage of supplies, the camera had to be introduced regionally and was nine months late in its national introduction. Then it was launched with a $9 million barrage of advertising. This included fourteen-page displays in the highest- circulation magazines and a series of television commercials featuring the English actor, Laurence Olivier—who reportedly received $250.000 for the first sales pitch he has ever made.

At the same time. Peter Wensberg. Polaroid’s senior vice president for marketing, started an ingenious campaign to woo the nation’s camera dealers, who traditionally have regarded Polaroid with distaste because they don’t get any photo-processing business from Polaroid customers.

Dealers are also annoyed by the fact that Polaroid products, because they are heavily advertised and their suggested retail prices well known, have been a favorite of discounters and department stores, which cut prices below wholesale in some cases. Faced with such competition, the camera dealers could not make money on Polaroid cameras and films—though the company’s heavy advertising created so much demand that they had to handle them.

Partners in the shop

Wensberg’s plan to overcome dealers’ antipathy was built around what the company labels its “partnership program.” Every dealer who sells the SX-70 must take a course that qualifies him to give a buyer a brief but thorough lesson in the camera’s use. He must also agree to keep a demonstration camera on hand, along with at least one trained salesperson. Once production makes it possible, he must maintain a certain minimum level of stocks. If he complies with these terms, the dealer—who pays $120 for the camera—receives an $8 bonus at year’s end for each camera he has sold. He gets another $2 per camera if Polaroid ’attains its own sales goal for the year. A dealer who sells an SX-70 at list price can enjoy a handsome total markup of $70.

The plan also applies to film, which costs the dealer $4.60 a pack and lists for $6.90. The year-end bonus on film can go as high as 10 cents a pack. A FORTUNE survey of dealers in several large cities reveals considerable enthusiasm for the program. Many say that they have never pushed Polaroid products before, but are now doing so.

So far, the public seems to have responded well. Admittedly, many early buyers were well-to-do vacationers (the camera first went on sale in the Miami area), and shortages continue to give ownership of the SX-70 a special cachet. One Miami dealer says he sold cameras to President Thieu of South Vietnam, Marlene Dietrich, John Connally, the Sultan of Oman, and Andy Warhol (who bought thousands of dollars’ worth of film and accessories).

Educating the users

Appraising a camera—and even more, color film—is a subjective business and the reaction of early users varies a great deal. One thing is clear: the camera is not an aim-and-shoot competitor of the Instamatic. Attentive care is required, especially in focusing, to produce good pictures. Buyers of the first cameras off the line had many complaints about the difficulty of achieving accurate focus. Eventually Polaroid modified its design to a split-image focusing system.

When the camera is used carefully and creatively, it can provide a photographic experience that few picture takers have had before. One important point that Polaroid marketers seek to drive home is that users should get closer to their subjects. The SX-70 lens is a slightly wide-angle one, and pictures taken from distances of ten feet or more are disappointing unless they are well composed. But close-ups can be extraordinarily good, with brilliant, grain-free colors and phenomenal sharpness. It takes instruction, however, to persuade the usual untrained photographer to move in close —and this is why Polaroid is cultivating the camera dealers so assiduously.

The user of the SX-70 has good reason to insist on high-quality pictures. Each photograph, assuming list price for the film and flashbar, costs 96 cents. This is considerably more than a standard Instamatic print, although not much more than a Polaroid 108 color picture. There is little question that the price of SX-70 film will come down over the next couple of years, if only because retailers will discount it. But the unit price of photos could generate some sales resistance.

The coming year should show just how strong the SX-70’s appeal is. Land insists that people will pay any price for a product that they really want—and he is certain that his new products will have that kind of appeal. It is easy to poke fun at some of his most expansive pronouncements—that the SX-70 someday will be used as much as the telephone, for instance. But Land has met scoffers before, and has vanquished them all.

The importance of the SX-70 for Land’s company can scarcely be exaggerated. Polaroid has a number of other profitable and growing markets, and has just begun to exploit its foreign oppor- tunities. Nevertheless, its top executives acknowledge unhesitatingly that the company’s future rests on the SX-70 and the family of cameras it will eventually generate. If all goes well, SX-70 camera and film will double Polaroid’s total sales over the next few years: 1973 sales were more than $650 million. Given the phenomenal margins—as high as 70 percent —that are possible on high-volume production of color film, profits could rise much faster. On the other hand, if the system does not capture the public’s fancy, it would not only be a serious financial setback but would give the company the appearance of being just another no-growth manufacturing outfit. Land’s own concept is that the company is a problem-solving, research-based organization that continuously develops new products to meet important human demands—frequently demands that are not even recognized.

Capstone of a career

Outsiders have long speculated about how well Polaroid would fare without its founder and inspirational leader. Land has given no hint that he will retire when he reaches sixty-five this year. Nor has he had anything to say about his successor, other than to insist that one of the two top men in the company should always be a scientist.

But even at Polaroid, there are no carbon copies of Land. He combines the prophet and the promoter, the egghead and the executive, in a way that is unique. The founder has, however, as- sembled an impressive team whose competence as a group may duplicate his personal talents. The SX-70 will almost surely be the crowning scientific achievement of Land’s distinguished career. If it also demonstrates the practicality of his corporate policies, Polaroid should keep right on trying to turn out striking new products for decades to come. END

Comments