Who designed the SX-70? (updated)

Dr. Land always envisioned an absolute one step camera, with no waste, no peeling, no nothing: press the button and take the picture But was the camera he envisioned really a foldable SLR? Who came with the idea of the foldable camera? Are there any predecessors of the SX70 as we know it? Who did the industrial design of the SX70? (Spoiler alert, no, it is not Charles and Ray Eames)

The back of this picture of Leonard Dionne says “1st COLOR PIC IN SX-70” but it is obviously a packfilm picture.

The back of this picture of Leonard Dionne says “1st COLOR PIC IN SX-70” but it is obviously a packfilm picture.

Mark Dionne, the son of Leonard Dionne says It is the only print in this set that does not have the batch number and “Polaroid” printed on the back. It could be one of the oldest prints in the public that was made with SX-70 film stock.

Which is then the first SX-70 picture?

Which is then the first SX-70 picture?

They both are: Welcome to the 9th floor, the secret laboratory where Dr. Land with a group of young engineers created the SX70.

The truth is that Dr. Land didn’t want a folding camera. In 1964 a young engineer named Alfred H. Bellows joined Polaroid. His manager was Dick Wareham. He was a wizard with mirrors and joined the effort to make the camera that Dr. Land had dreamed of the size of a Cross pen and pencil set: no waste film, and no bellows on the camera.

Enter the Lens and Bellows unit.

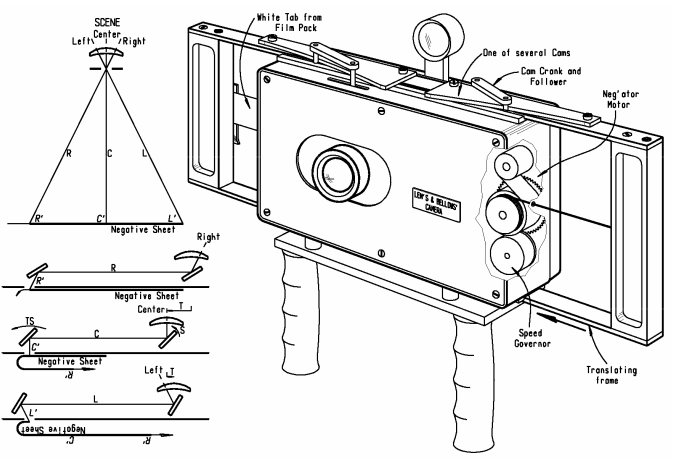

Lens and Bellows camera

In Alfred Bellows own words: I quickly set about designing this revolutionary new camera. As the design took form, Wareham arranged for one of the best model makers in our shop to build the hardware—the Len of “Len’s & Bellows’.The project moved so efficiently and rapidly that, miraculously, we were taking pictures with a scanning camera in less than six weeks. Wareham was so pleased with the results that when Land asked him how the camera was progressing, he invited me to go with him to present a functional demonstration. What excitement. Land was excited, too, and over the course of the meeting managed to figure out which way he and Bill McCune should respectively walk to make himself look thinner and Bill, the health and exercise zealot, look portly. (Scanning cameras distort any objects that move during the scan.)

The LEN’S & BELLOWS’ CAMERA, a scanning camera constructed in 1964 and ’65 and drawn in perspective from memory in 2012 by its inventor Alfred Bellows. Inset at left shows a conventional camera’s optical system followed by three progressions below of the scanning system as it successively simulates the conventional optics. For scale, the “box” portion of the camera measures 7.5 by 4.4 by 1.8 inches.

If you want to know more about this camera, unfairly forgotten by history, I highly recommend the book An Engineer’s Life: One Man’s Tale of Adventure

In Bellows own words:

In August 1966, our small design team of one engineer (me), three designer/drafters, and a model maker was suddenly enlarged to a project total of 19 and moved across Main Street to the ninth floor at 565 Tech Square.

Dick Wareham was the manager, I was the senior engineer, and there were 2 junior engineers, 4 designers, 6 drafters, and 5 model makers including Len with a well-equipped model shop.

Unfortunately the scanning camera was slow (⅓ of a second for picture taking) and had a lot of challenges that ultimately killed the project.

All told, we worked on scanning cameras from November 1965 until June 1967.

I find the “Len’s and Bellows” camera an amazing feat of ingenuity, something that probably the engineers that worked on the project suspected would never work, but still they complied to Dr. Land to the end, up until the man himself acknowledged that it was not viable. The nail on the coffin was probably integral film, since that made the system, initially tested with packfilm, totally impractical.

Folding camera concept: “Finally he heard you!”

So we come to the gist of the question. When was the concept of the folding camera devised and who did it?

In my understanding the idea was time and time again suggested by Al Bellows and Dick Wareham only to be dismissed by Dr. Land. But then Al Bellows recalls:

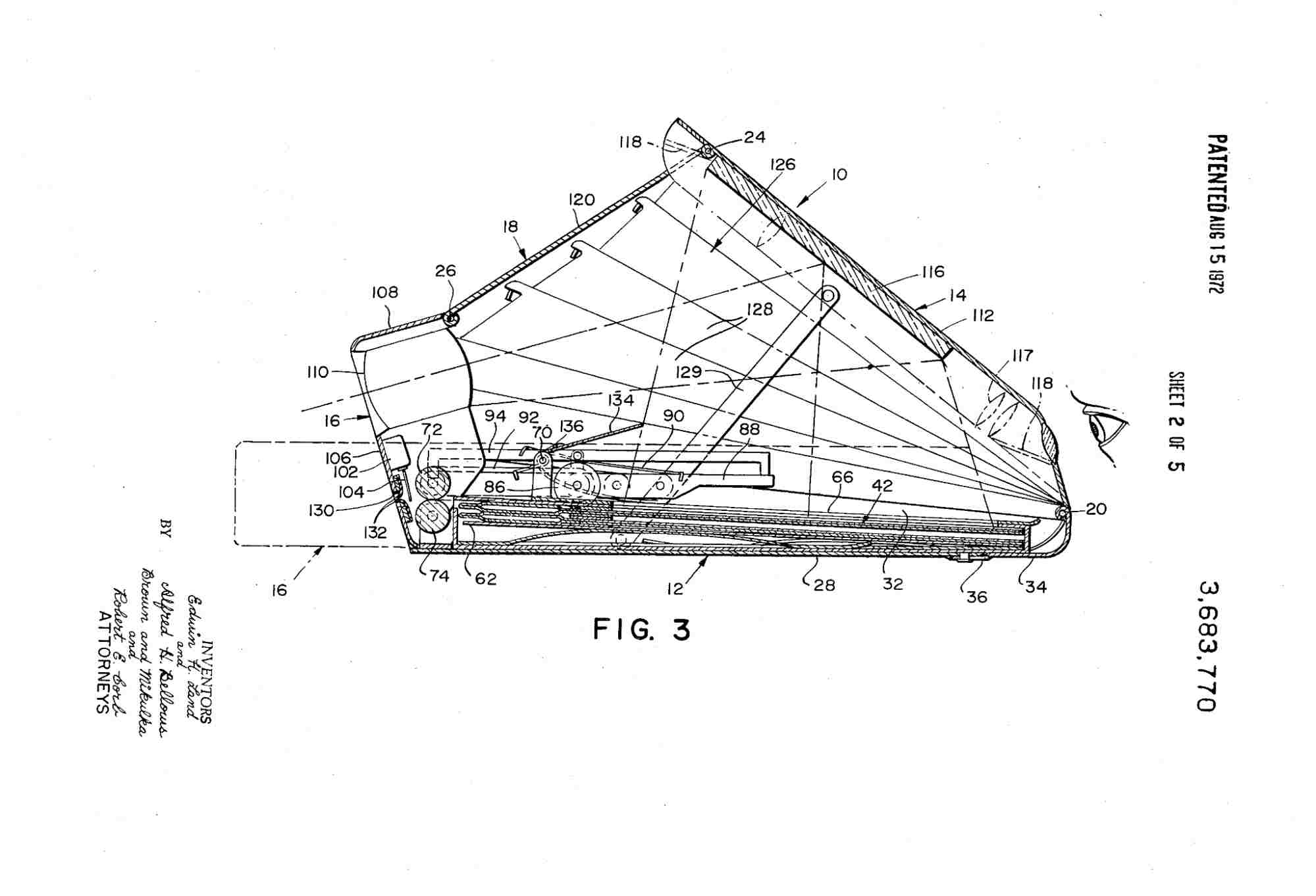

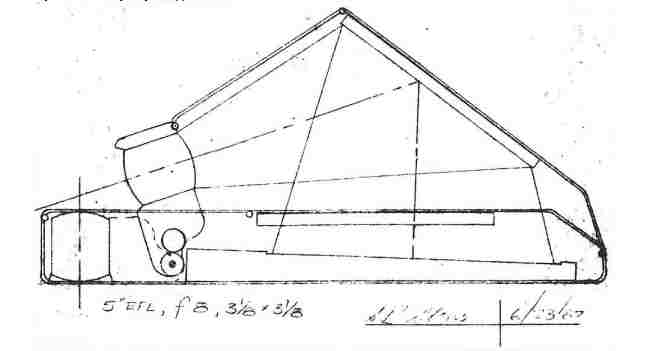

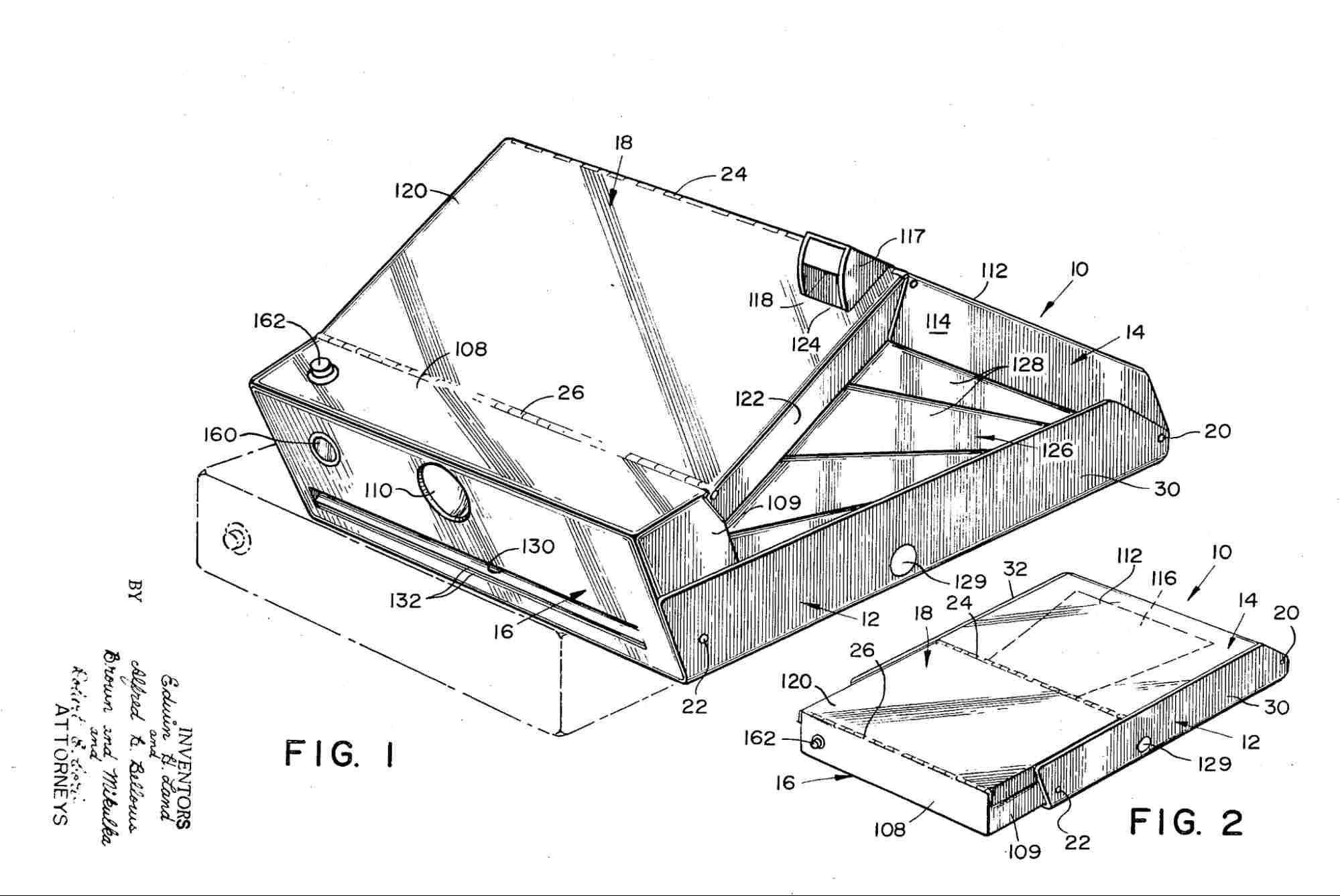

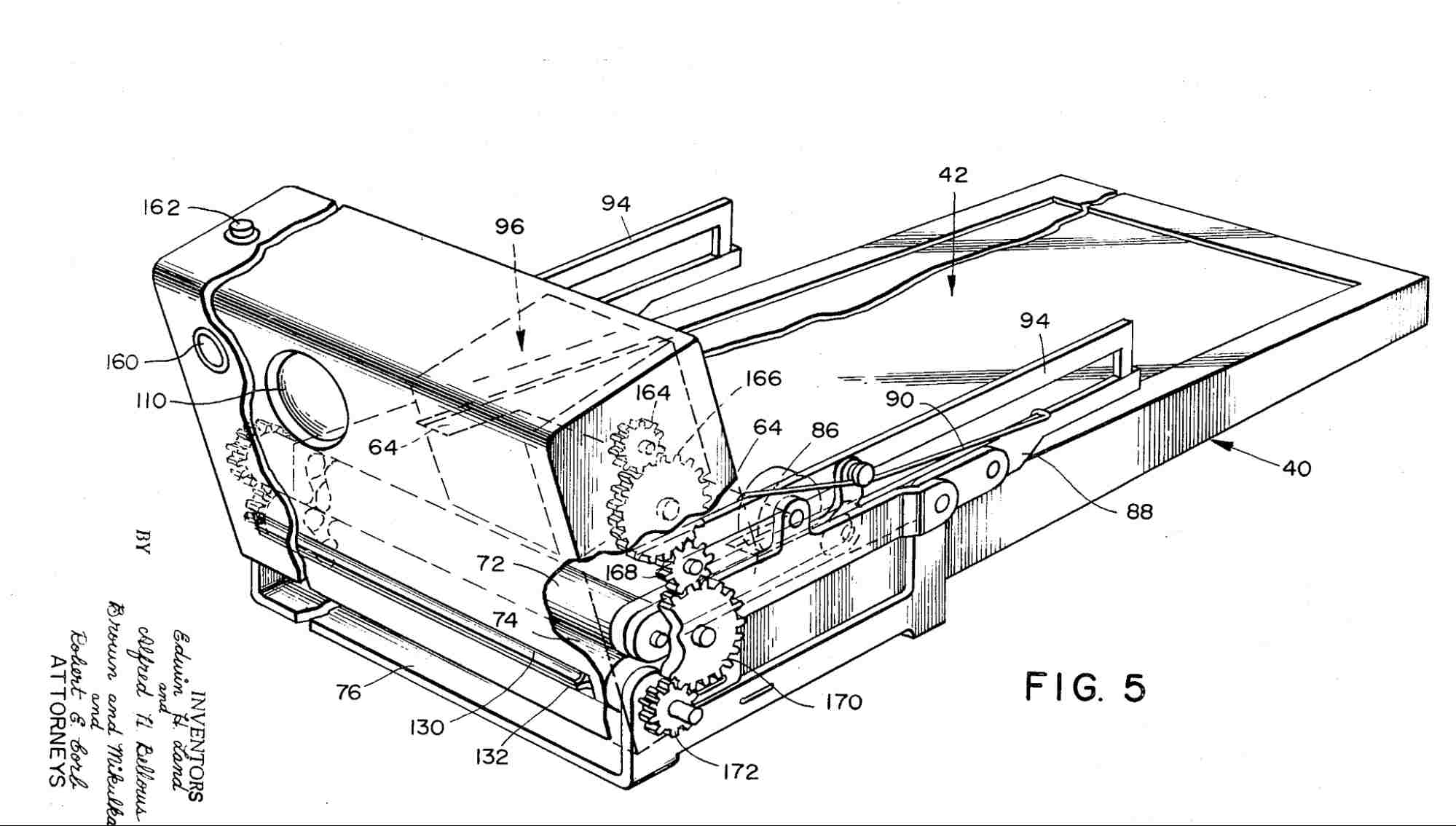

During a vacation to California, Dr. Land called: (…)he proposed a design in which the optical path was folded at its midpoint by a relatively large mirror and the lens tucked down close to the spread rolls. The mirror-holding panel and shutter panel were part of a four-bar linkage that would collapse flat to resemble his original objective of a flat camera that would fit in a pocket or purse. Wareham had been following our discussion on the extension phone, and when Land and I finished the call, he came out of his office, gave me a high sign, then came over to my desk and said, “Finally, he heard you!” After these calls, it was my follow-up job to make sketches and to critique the idea. This particular idea was no exception, so I went to work. And the full-scale layout worked. Thus was born the SX-70 as it eventually came to market. (US Pat. No. 3,683,770 to Land and Bellows was filed a few weeks later, though it took years to issue.)

Alfred Bellows original drawing of the SX-70, June 23, 1967 from his book. It is absolutely clear that Bellow was the first one to sketch these design.

You can see Alfred Bellows name in the patent.

They made a few prototypes, one of wood and aluminum to test the folding action and another non-foldable to test picture taking. Since the opacifier was not invented yet, they figured out a small box to develop the picture prior to exposing it to the light.

Even while on vacation, some of these prototypes were overnight to Dr. Land still in California.

Some of the features of the final camera are already there. Of course some “details” had, at the time to be figured out, like an opacifier that would allow the concept of the film unit, as needed by such camera design to be possible, or a viewfinder.

Viewfinder

The folding design was a compromise in Dr. Lands mind, no doubt, and the was still the question of the viewfinder that had to be addressed.

Again in Bellows own words:

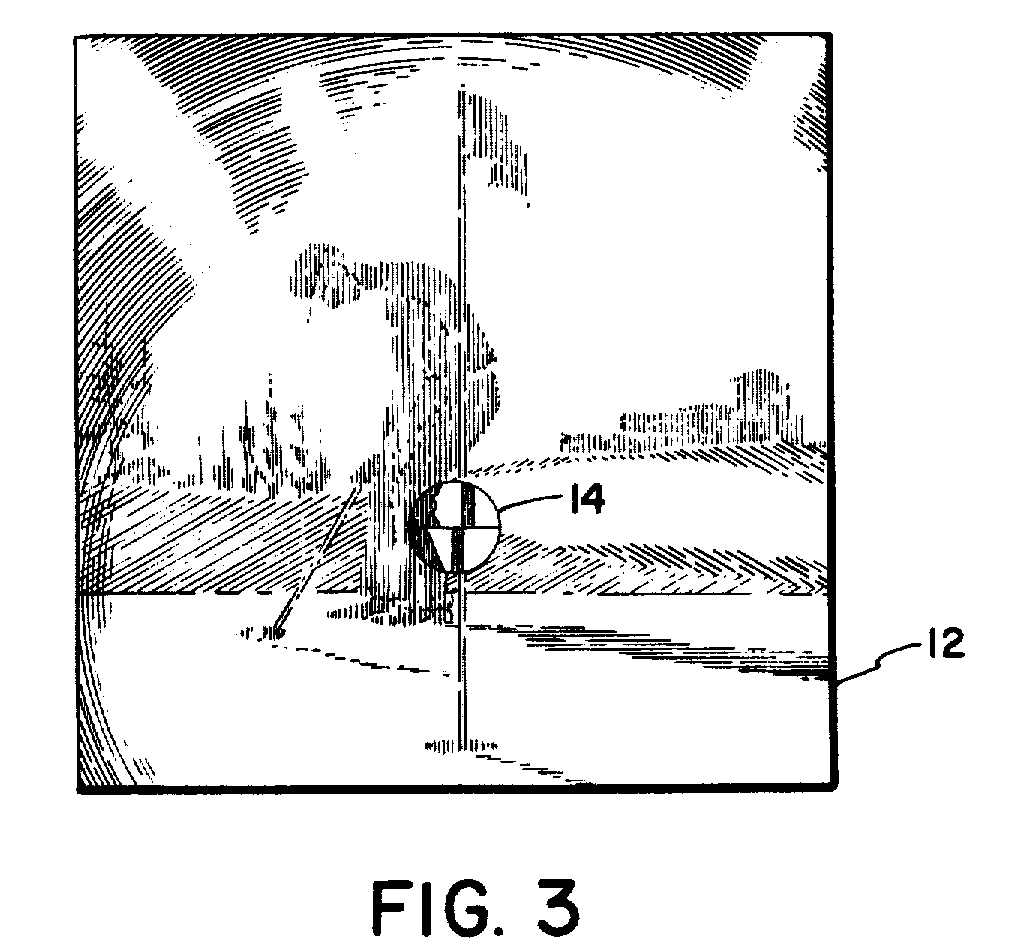

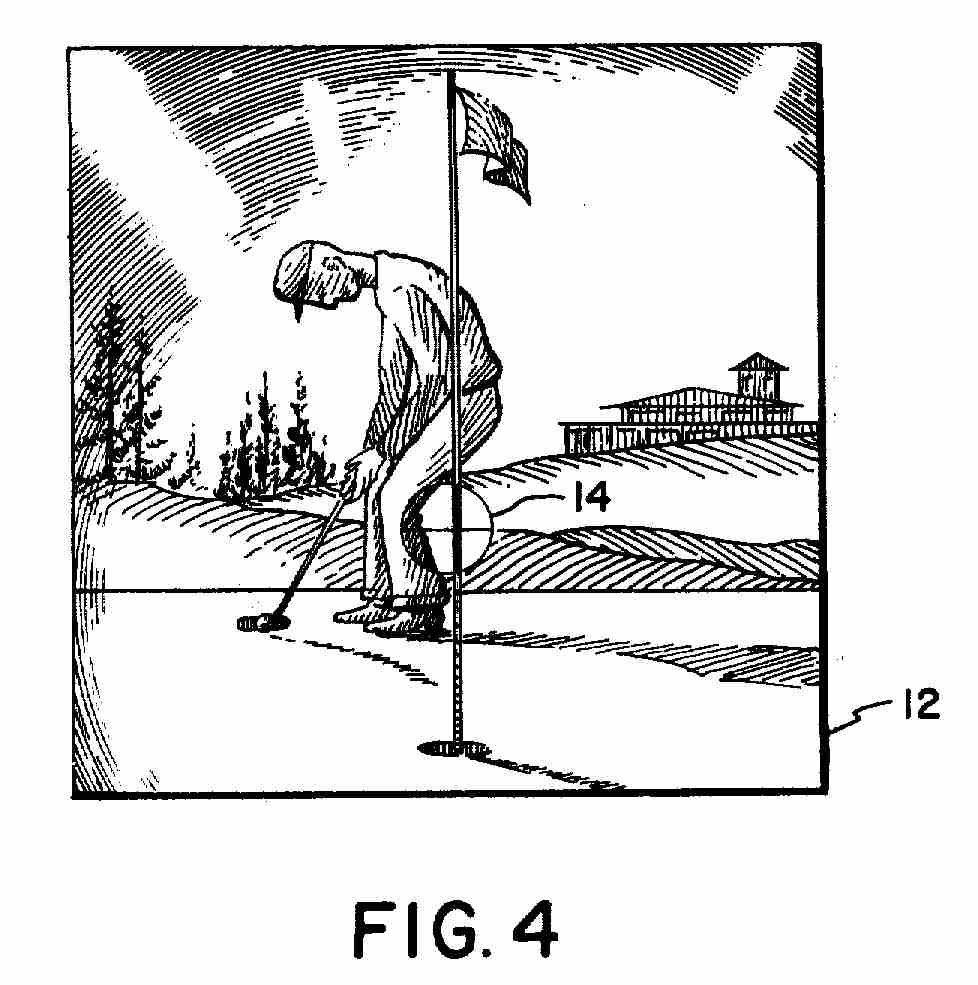

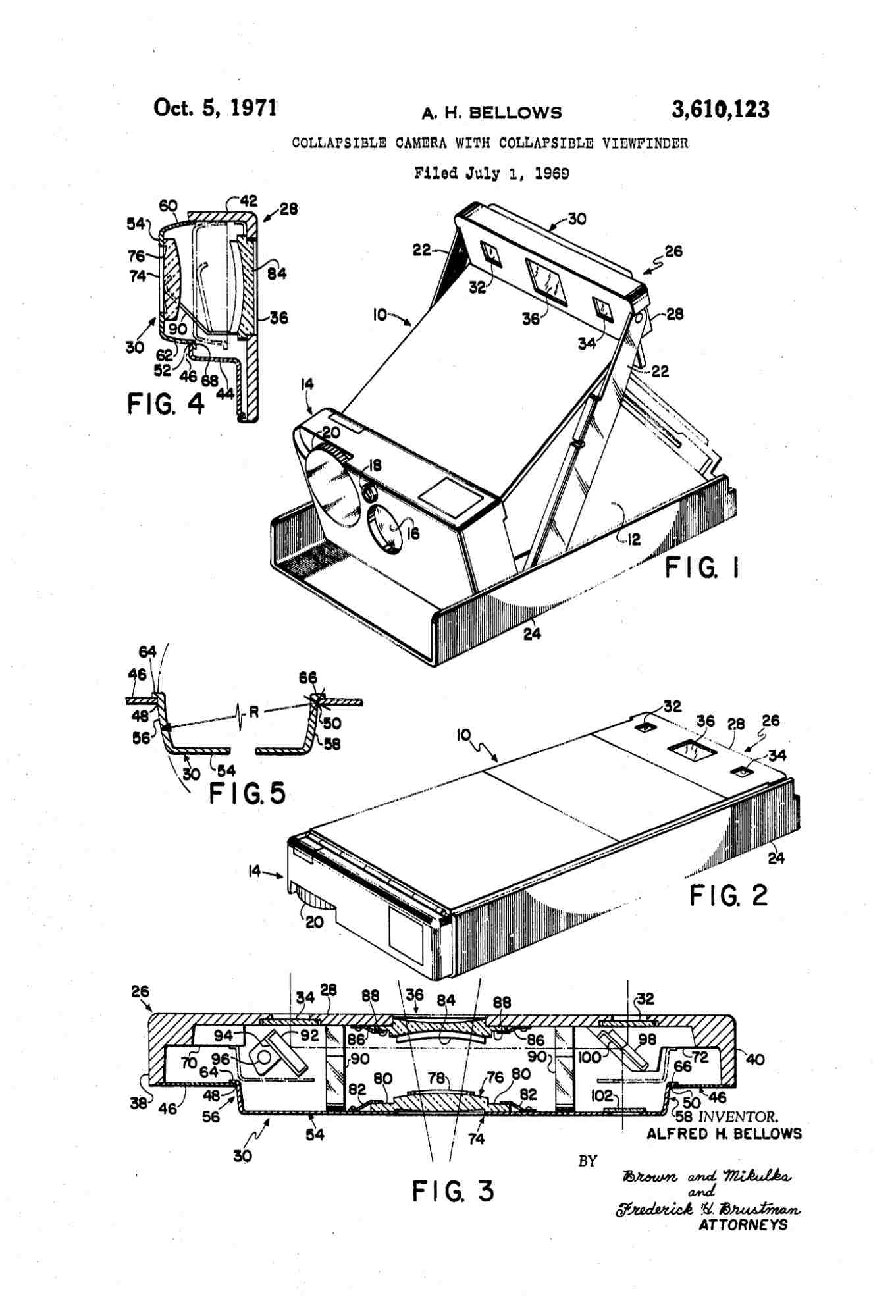

By this time my assistant Phil Norris (I thought for a while that he was referring to Phil Baker, the author of the amazing book From concept to consumer ) had fully joined the challenge of developing a good viewing system. Many configurations were hypothesized. Most anticipated an eye window either at the very back (as in Fig. 3 of US Pat. No. 3,683,770), requiring the camera to be held in a cantilevered position against the bridge of the nose; or near the roof-peak (as in Fig. 1 of US Pat. No. 3,610,123 also on back cover upper right), allowing the cheek to rest on the back roof surface, but requiring that the head be tilted forward and the eye rolled upward.

Both of these positions were quite remote from the lens with the need of an optical or mechanical linkage from front to back for viewing, ranging, and parallax-correction.

For rangefinder links, flexible shafts, levers, and hydraulic lines with tiny bellows at each end were proposed and modeled. All told, there must have been two dozen or more proposed solutions for framing and ranging, few of which were promising.

One of the rangefinders that Land encouraged was a stereo version that utilized both eyes for determining distance. In the end, I designed two versions, which were installed and tested on a 100-style camera for ease of demonstration (see US Pat. Nos. 3,622,242; 3,680,946; and 3,610,128, illustrated atop a ColorPack Land Camera). The first of these adjusted the convergence of a virtual target formed by an arrow-shaped reticle, and projected that target in such a manner that it would appear to move toward and away from the camera with focus adjustment. The rangefinding was accomplished by the photographer adjusting the camera until the projected arrow appeared to be at the same distance as the subject. It was quite accurate, but not entirely satisfactory to me. Therefore, I built another version that not only adjusted the convergence but also the accommodation (focus) of the target in synchrony with the convergence. Not only did the arrow appear to move toward and away from the camera, but it was always in the correct focus for the corresponding distance. This version was gangbusters. I even asked an engineer with one glass eye to try it. At first he laughed at me and refused to even look through it, but ended up being quite consistent with adjusting the range—presumably by comparing the focus of the arrow with the focus of the subject. Dr. Land reported to me that Edward Purcell, the Nobel Prizewinner from Harvard used this rangefinder and commented, “…best from Polaroid in years.” As successful as the stereo rangefinder was technically, it never made it into the SX-70 Land Camera or any other Polaroid Land Camera.

The bar-type viewfinder/rangefinder had a distinct disadvantage with respect to parallax and accurate ranging when used with a lens that focused so close. Also, Land was never particularly happy with that model.

Therefore, he invented a single lens reflex viewer with an eyepiece at the camera’s peak for looking down at a focusing screen just above the film plane. This concept required much greater complexity of both the mechanism with its multicycle shutter, flipping mirror, and folding viewer; and the optical system with its off-axis aspheric lens and mirror. The design and development for this optical system was largely done by Baker and the Henry Street Optical Division (One piece of this new configuration, the film-loading door, can be seen in US Pat. No. 3,643,565, which covers and claims my misslatching-proof switch design for ejecting the dark slide. It is also seen in the lower left figure on the front cover.)

Industrial Design, Dreyfuss

Many people think that Charles and Ray Eames, author of the famed film about the SX-70 did the industrial design of the camera

SX-70 design is credited to Henry Dreyfuss Associates and specifically to James M. Connor in the firm of and, of course to Edwin Land himself. .

This is not the case, as in all things SX-70 many people contributed to the final design, people like Al Bellows, and the shop department run by Len Dionne. There is an amazing collection of pictures of Len Dionne’s model shop thanks to his son Mark. Len was the wizzard behind all those prototypes and early tests.

But as far as industrial design goes, it is thought to be one of the final projects in which Dreyfuss personally participated: The SX-70 “was to be the last product worked on by Henry Dreyfuss (1904-1972) before his untimely death.” (P. Baker)

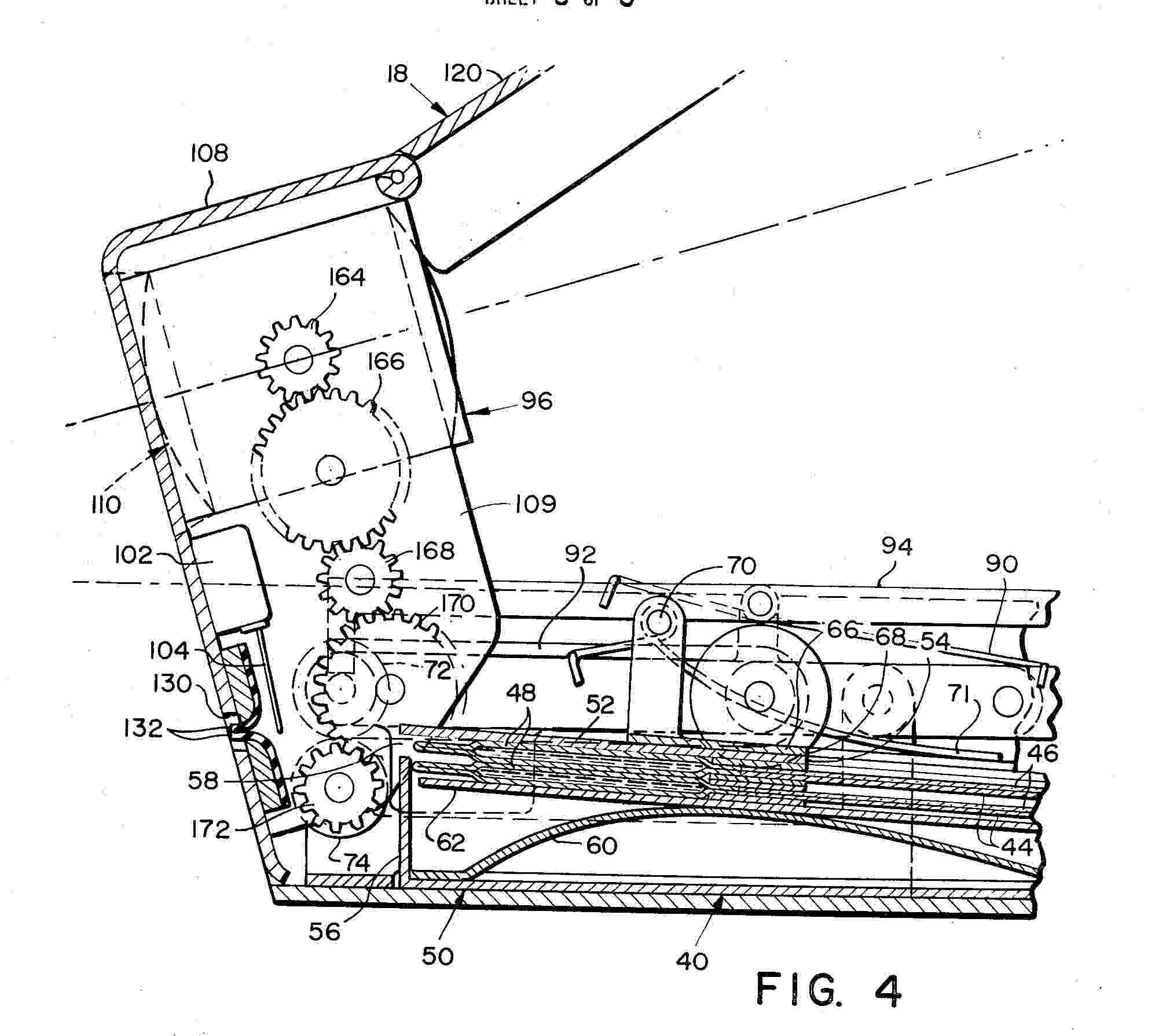

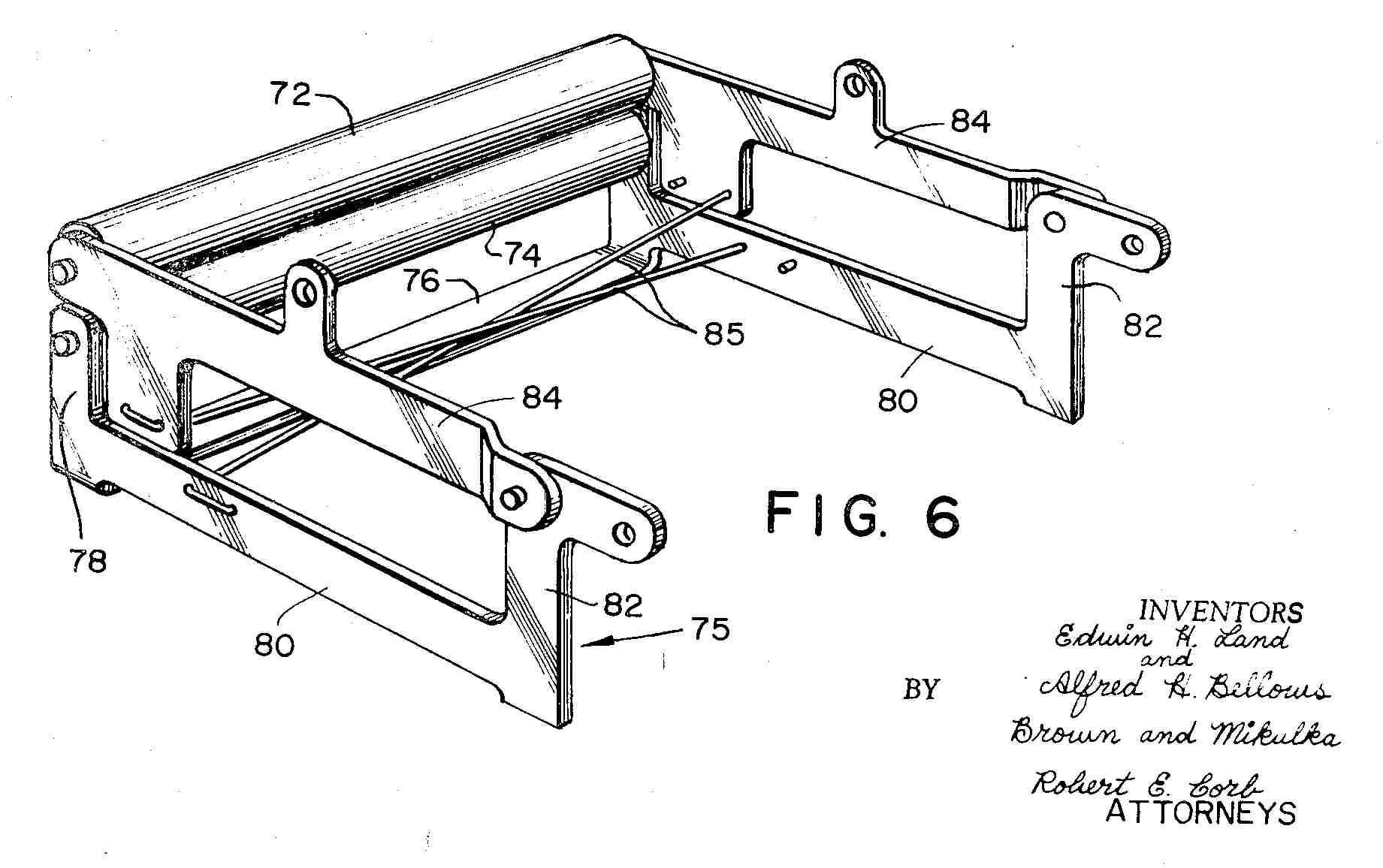

Al Bellow knows: The first fully developed camera design was styled with the help of Jim Connor of Henry Dreyfuss Associates, the industrial design firm in NYC that had styled all telephones of that time, many John Deere machines, Honeywell’s round thermostat, etc. This camera folded down into a U-shaped tray running the length of the folded shape (see US Pat. No. 3,610,123 and back cover upper right). It was opened by lifting the viewfinder/rangefinder “bar” at the back end, thereby raising a pair of pivoted links that in turn lifted the other components into place. The finder bar had a telescoping section in the back that I devised in a manner that could not jam—famous last words, right? But it did work. (See Figs. 3, 4, and 5 of said Pat. 3,610,123) This was the first working SX-70 camera to approach a realistic level of utility. It had all the basic pieces needed for a product, and some soft-tooling was being made for prototype manufacture. (Bellows)

Phil Baker says about Dreyfuss:

I admired how Dreyfuss’s designers were able to make a product come to life, giving it a unique personality and look. During the development of the SX-70 camera, Dreyfuss worked with Polaroid’s Founder and CEO, Edwin Land to influence its shape, how it folded, and how it was held in the hand, as well as the innovative leather covering and brushed chrome finish.

On many of the products I developed, Dreyfuss was adept at turning a boxy design into something distinctive and memorable. The product often looked less intimidating and more inviting, yet still conveyed what it was supposed to do and how it worked.

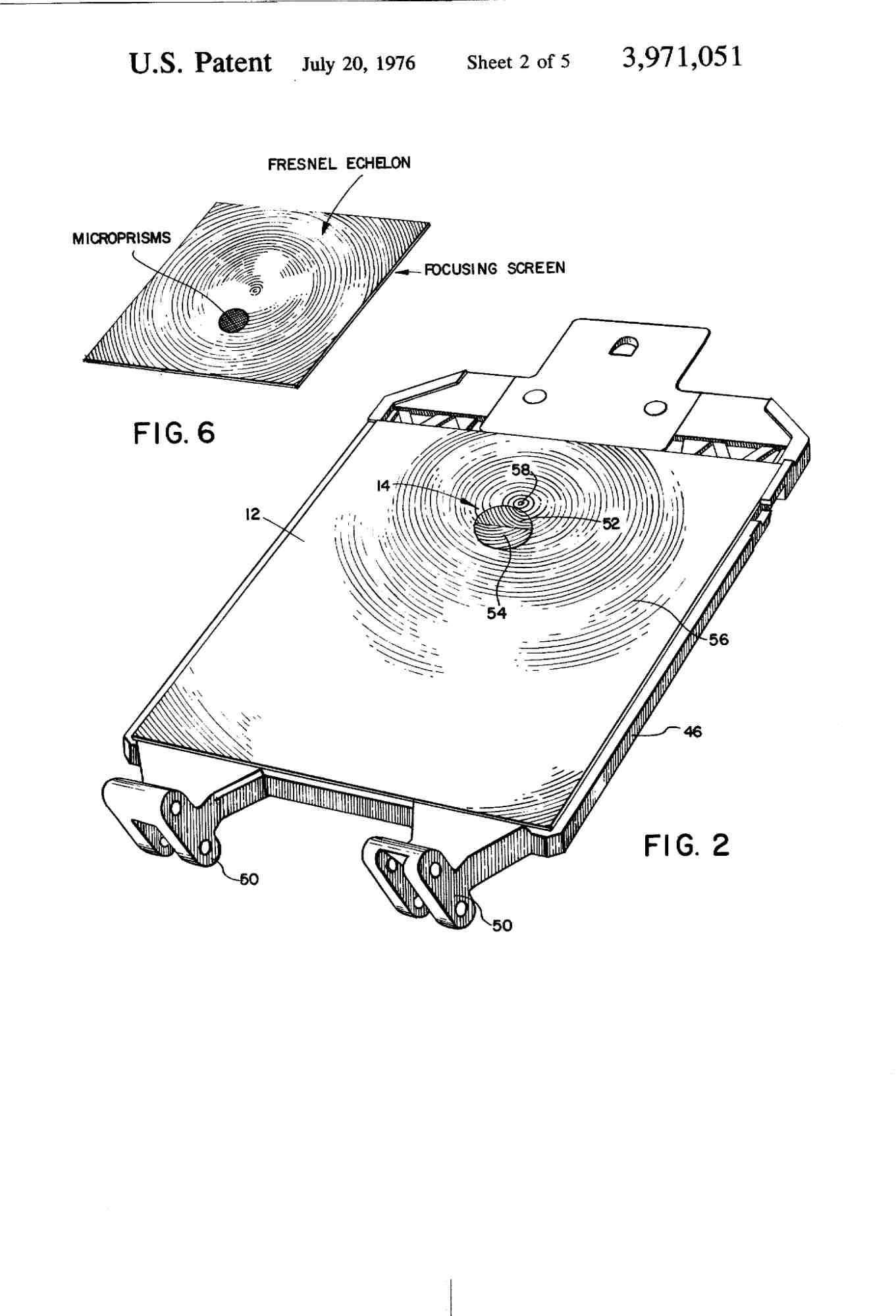

The focusing screen

Formerly, complex electro-mechanical consumer products took years to develop. Polaroid’s SX-70 camera, their first to fold small enough to fit in a jacket pocket and use film that didn’t need to be peeled apart, took more than five years to engineer. (…) The Polaroid SX-70 camera went through years of development, but not until it got into the hands of users did the design team realize how serious a deficiency it had. Actually a few knew, including myself, but those closest to the project failed to grasp its importance.

I was running Polaroid’s test labs during the year prior to the SX-70’s introduction. As part of testing the camera using a variety of first-time users, I found many had diffi culty accurately focusing using the SLR-like matte screen. Dr. Land designed the camera so the image would appear out of a fog and come into sharp focus as the focus wheel was turned. He wanted to replicate how the image would emerge on the actual film as it was developing.

However, the focus was also used to set the flash exposure, and the exposure was much more sensitive to getting a precise focus. As a result about 30% of all flash pictures were unacceptable, being either too dark or completely washed out. I quickly put together my findings and thought it would be catastrophic if the product went to market. I took the findings to Dr. Land’s assistant and the SX-70 design team, and showed them my conclusions. They all politely thanked me but said they had been working on the product for years and hadn’t seen similar results. If it turned out to be a problem, we’d just have to teach customers to do a better job focusing.

Pure denial.

But my analysis had shown that the focusing system was not capable of even an expert getting good results. I naively thought the company’s burden was on my shoulders, although few others seemed to see things as dire.

After a few weeks of experimenting, I came up with a solution. It involved modifying the focus screen in a way to provide a split-image focusing aid that quadrupled the accuracy, sufficient to get good exposures. I added it to a camera, tested it, and it worked. I showed it to Land’s assistant, and he seemed impressed. But he said I could not show this to anyone or I could be fired. The visible focusing element went against Dr. Land’s vision of the image coming out of the fog, and if Land heard about someone working contrary to this, that person’s job might be in danger.

I had done all I could do. I identified the problem and then found a solution, but others were not willing to recognize that there was a problem, at least not just yet.

The product came to market a few weeks later, with the only negative news being that it had a serious exposure problem, but was otherwise well reviewed in a hugely successful PR campaign which included Dr. Land and his SX-70 appearing on the cover of Life magazine.

A month after the product went on sale I got a call to go to Dr. Land’s office with my prototype. He said to me that he heard that I had a solution to the exposure problem and asked me to show and explain it to him. He looked into the camera and tried it out, saying nothing.

After 5 minutes he told his assistant that we would incorporate this into the SX-70 as a running change, but locate it below the center of the image so as not to make it too noticeable. He congratulated me for my efforts and said we would have to find another solution that would eliminate the visible focus aid entirely.

The new fix was phased in a few months later. However, Dr. Land was still unhappy that his original vision had to be abandoned, so a year later he introduced the first camera to have an auto-focusing system, eliminating the need for my focus aid. To this day, one of my most memorable patents is as co-inventor with Dr. Land for a focus aid located below the center of the picture.

What this demonstrates is that those close to a product, even one of the most famous inventors of all time, often can’t see or accept the flaws in an invention, or perhaps, more appropriately, his baby. However, once forced to do so, a brilliant inventor such as Edwin Land turned a defect into a challenge and used it to spur further innovation. But even for him to see the problem, he fi rst had to get it into the customers’ hands to be convinced. (…) I admired how Dreyfuss’s designers were able to make a product come to life, giving it a unique personality and look. During the development of the SX-70 camera, Dreyfuss worked with Polaroid’s Founder and CEO, Edwin Land to influence its shape, how it folded, and how it was held in the hand, as well as the innovative leather covering and brushed chrome finish.

On many of the products I developed, Dreyfuss was adept at turning a boxy design into something distinctive and memorable. The product often looked less intimidating and more inviting, yet still conveyed what it was supposed to do and how it worked.

Comments