Inspiration

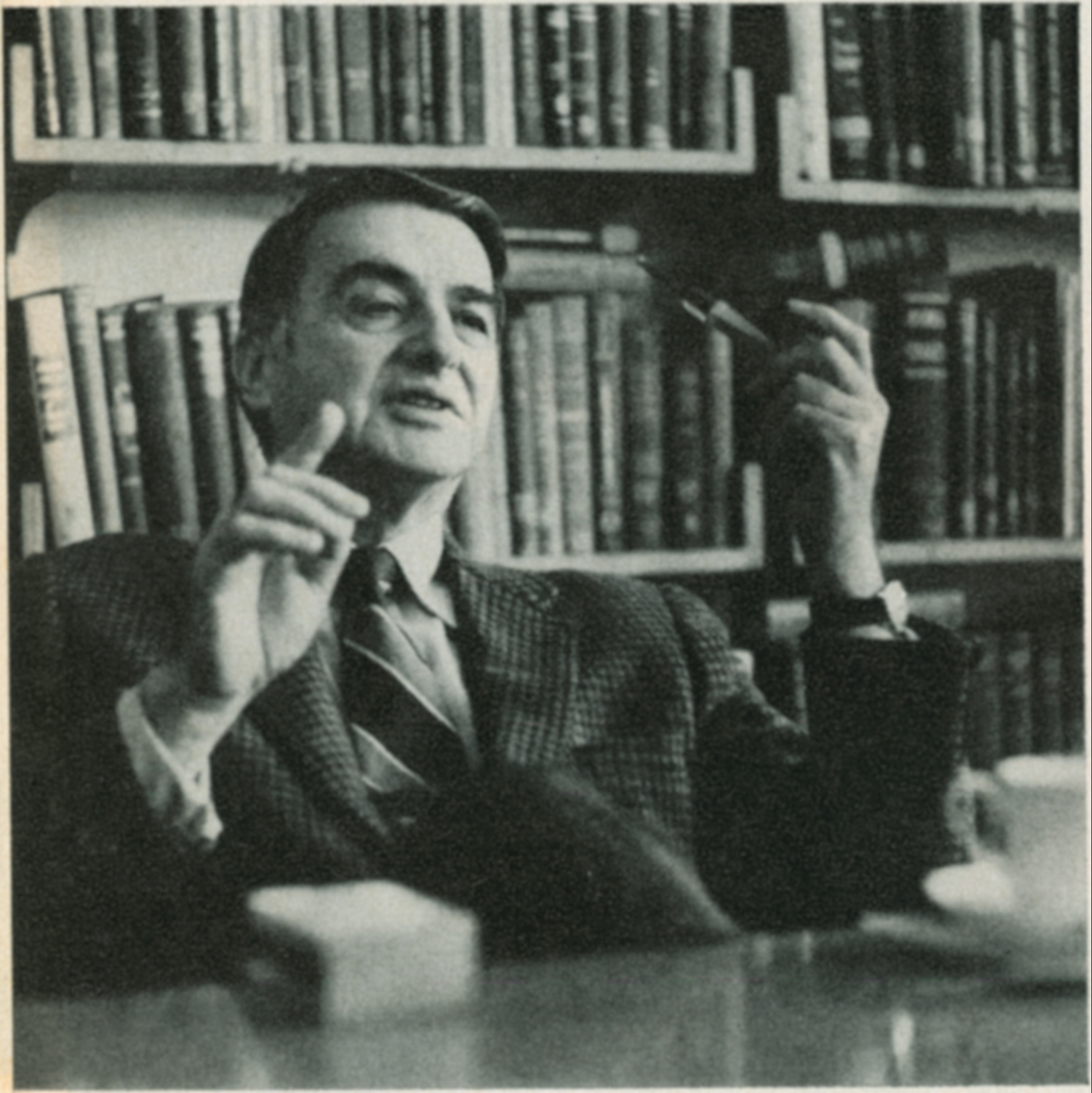

In early October 1972, Sean Callahan of LIFE magazine interviewed Dr. Land in his Cambridge office.

When I meet someone for the first time, often I can tell right away whether he may be a potential scientist. In talking to this person, how much is he ahead of you? When you draw a breath to say the next thing, does he know what you are going to say before you say it? Does he delight in the construction you are making? Does he turn the conversation quite subtly because he perceives where it is going and wishes it to go somewhere else? Not all scientists are that alert. There are many scientists who, for all their marvelous training, are just plain dull. You sit with them and nothing is happening. They have been stultified somehow and the world is going by them. (…) When Arthur Ashe plays tennis, his purpose each day is to play the game in a way he has never played it before. It may be a backhand he uses, one that he may never have used before in that circumstance. His play is a fresh integration of his world at the instant of action. A really great scientist has the whole past at his disposal. At any instant he is rebuilding the world, molecule by molecule, in his subconscious. That is what you want in an athlete or a scientist. An essential aspect of creativity is not being afraid to fail. Scientists made a great invention by calling their activities hypotheses and experiments. They made it permissible to fail repeatedly until in the end they got the results they wanted. In politics or government, if you made a hypothesis and it didn’t work out, you had your head cut off. The first time you fail outside the scientific world you are through. *Many people are creative but use their competence in ways so trivial that it takes them nowhere. Their kind of creativity is not cumulative. True creativity is characterized by a succession of acts each dependent on the one before and suggesting the one after. This kind of cumulative creativity led to the development of Polaroid photography. One day when we were vacationing in Santa Fe in 1943 my daughter, Jennifer, who was then 3, asked me why she could not see the picture I had just taken of her. As I walked around that charming town, I undertook the task of solving the puzzle she had set for me. Within the hour the camera, the film and the physical chemistry became so clear that with a great sense of excitement I hurried to the place where a friend was staying, to describe to him in detail a dry camera which would give a picture immediately after exposure. In my mind it was so real that I spent several hours on this description. Four years later we demonstrated the working system to the Optical Society of America. All that we at Polaroid had learned about making polarizers and plastics, and the properties of viscous liquids, and the preparation of microscopic crystals smaller than the wavelengths of light was preparation for that day in which I suddenly knew how to make a one-step photographic process. I learned enough about what would work in enough different fields to be able to design the camera and film in the space of that walk. If you are able to state a problem—any problem—and if it is important enough, then the problem can be solved. Long before he puts the problem into words, the scientist knows how to confine his questions to ones that he thinks are answerable. He wouldn’t be able to formulate them otherwise. His taste, discernment, wisdom, shrewdness and experience have established within him an inner knowledge of what is feasible. However, you must pick a problem that is manifestly important. It must be important to you and your colleagues, and more important than anything else. You can’t necessarily separate the important from the impossible. If the problem is clearly very important, then time dwindles and all sorts of resources which have evolved to help you handle complex situations seem to fall into place letting you solve problems you never dreamed you could solve. Some people feel that the Polaroid camera is strictly an amateur product that does nothing to develop the artistic expression of photography. What I contend is that far from taking creativity away from people, we provide an opportunity for creativity that other photography doesn’t allow. Previously the only people who could become good photographers were those who had the time to teach themselves to record the image, develop the negative and make the print, embodying their own visualization of the world. Photography is unlike any other art form. In the other arts there is always a continuous interplay between the artist and his art. He has the painting or sculpture before him. What we have tried to do is to provide a medium for “artistic expression’’ to anyone with only a reasonable amount of time. By giving him a camera system with which he need only control his selection of focus, composition and lighting, we free him to select the moment and to criticize immediately what he has done. We enable him to see what else he wants to do on the basis of what he has just learned. The only reason I did all of this is because I knew I loved to take pictures and there just wasn’t any good way of doing it.

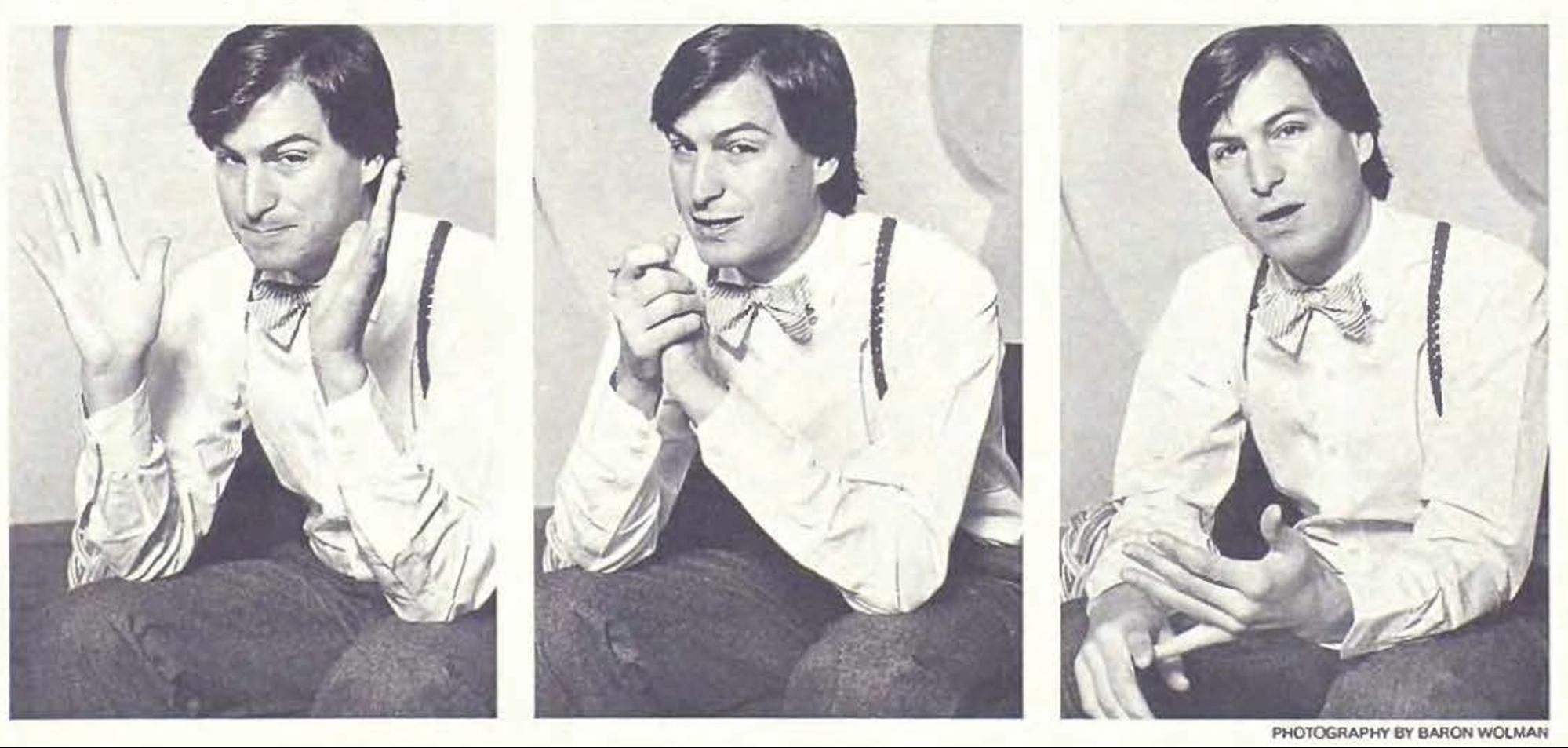

In February 1985 David Sheff interviewed Steve Jobs for Playboy.

These are the extremely bright individual contributors who were troublemakers at other companies. You know, Dr. Edwin Land was a troublemaker. He dropped out of Harvard and founded Polaroid. Not only was he one of the great inventors of our time but, more important, he saw the intersection of art and science and business and built an organization to reflect that. Polaroid did that for some years, but eventually Dr. Land, one of those brilliant troublemakers, was asked to leave his own company—which is one of the dumbest things I’ve ever heard of. So Land, at 75, went off to spend the remainder of his life doing pure science, trying to crack the code of color vision. The man is a national treasure. I don’t understand why people like that can’t be held up as models: This is the most incredible thing to be—not an astronaut, not a football player—but this.

December 4, 2003, author William Gibson said in an interview to The Economist

The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed.

Daniel Arsham: Polaroid (Future Relic 06), 2016

The larger than life figure of Edwin Land is an inspiration for me and has guided, silently, my journey these past years. Land was not only a futurist but an optimist, he was already in the future. It is difficult not to see that the ever ubiquitous camera that he dreamt in 1970 is in 2022 the smartphone: a camera not only to take amazing pictures of people but to document every day life. A camera to socialize photography, making the picture taking process seamless.

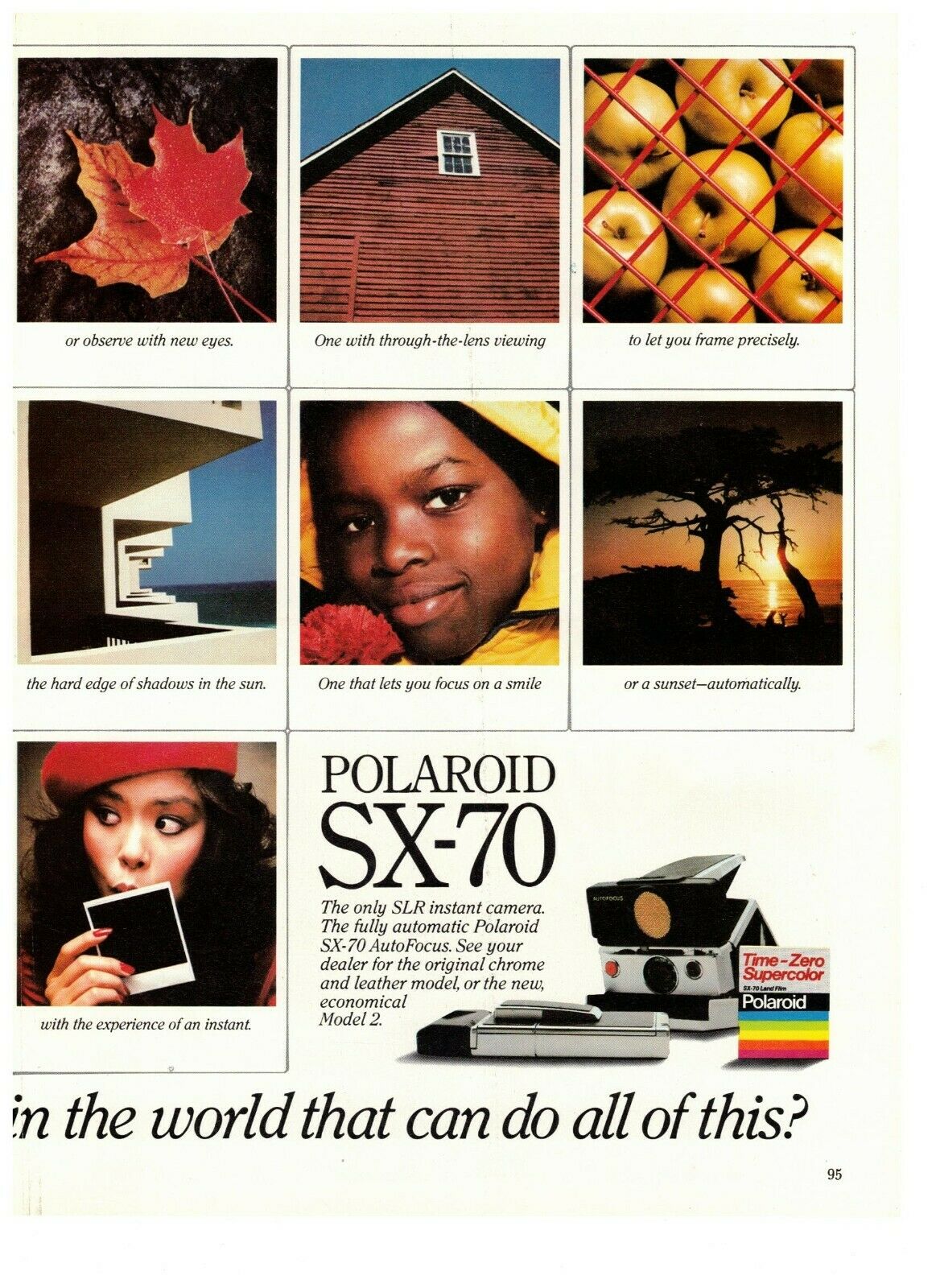

Maybe it was digital, maybe it was cheap 1-hour photo, maybe it was the army of pencil pushers that followed Land. The fact is, Polaroid lose its mojo. Maybe it’s the fact that when you are so far ahead into the future as Dr. Land was, the future is your own worst enemy. So now the question is: where does it come our modern fascination with all things instant photography in general and SX70 in particular?

Same as the invention of photography in the late nineteenth century was a major factor in the advancement of impressionist movement once photo realistic images were no longer a goal, painters look for something else. Nowadays digital photography has had a similar effect in photography as an art, digital pictures are too perfect, digital manipulation of images turn out “impossible” pictures, sometimes it is accomplished on camera, due to computational photography, so now we are in a place where the way forward is to take a step back, thus the comeback of instant and analog (or silver) photography in general (although I like to call it slow photography).

In this crossroad, the SX70 is perhaps now more relevant than ever, where an imperfect media (I love you Polaroid, please show me your love) seeks its perfect tool: but now the goal is different, we want, we need something different from the original tool, where automation was the goal, now we want control, and that control can come in many flavors, where an all-in-focus was a requirement, spending a lot of time and money developing a pneumatic system. But now, maybe, just maybe, we want bokeh, shallower depth of field, faster shutter.

This is my way of saying why going back to the origins and knowing as much as I can about the camera is what lets me go forward way beyond what’s been done. And I say it with all my heart, you can fake it, but it’s way more fun my way, to feel the connection, to speak with the people that were in the room, I remember Peter Carcia, telling me that he was working late on the Y-delay, way past 2am, and the phone ringing. Pete of course assumed that it was his was his wife, but it was Dr. Land, and Pete saying Dr. Land “it will be done by tomorrow” and Dr. Land replying “Pete it is already tomorrow” (I am paraphrasing).

Comments