The magic number and AUTO exposure

In the beginning it was all about manual. Making the marvelous SX70 work with manual shutter speeds.

And we have accomplished that, and then some, openSX70 was the first to do double exposures, no mechanical modification to do full F.8 flash with studio strobes, self timer… all really really cool stuff.

so… why auto?

So maybe many of you wonder why getting “auto” was so important to me. Or why, it is important in general: personally I love to shoot manual, usually use my iPhone as a light meter, and I love it, but it is true that are many many situations where you just want to take the shot, and probably a well calibrated camera will take a better shot that you due the circunstamces. But the answer is much simpler (being obnoxious here and paraphrasing JFK): Why climb the highest mountain?

Another answer, may lie in the fact that we can agree that the characteristics of the original -I mean true- Polaroid film are simply different from what we have to use now, some say SX70 film is 100ISO, others 125 or even 160ISO, and something similar with 600, so maybe modern sensors can deliver a better measurement and thus better pictures. Who knows.

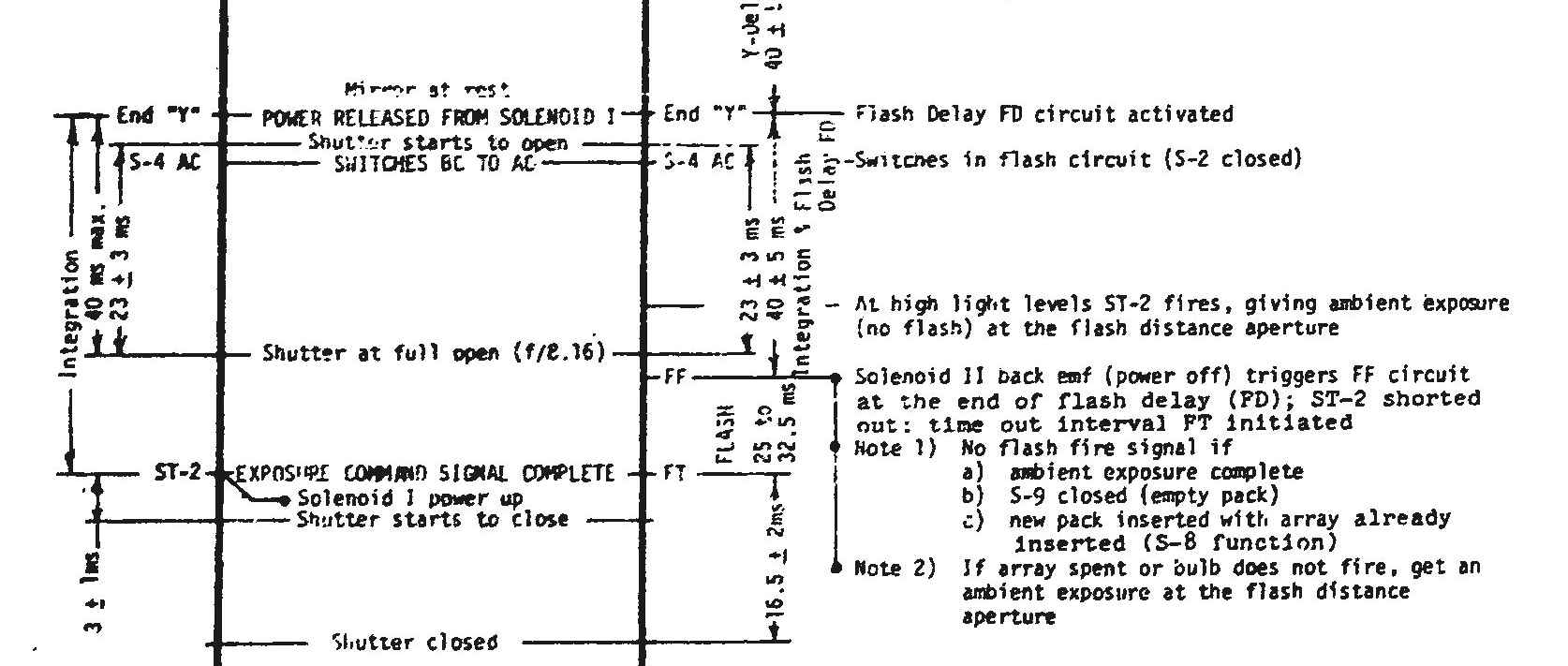

Auto exposure has its challenges because of the way the “inefficient shutter” of the SX70 works. I try to explain it in a post.

Many already know that I have been struggling with it from the beginning, the first sensor I chose the BH1750, is one of the modern crop of sensor, the don’t give a voltage or a current not even a frequency, they just say the value in lux. That meant problems for me from the get go, the values, after al the stuff in the camara (dark/light assembly) was too low and inexact, and it was damned slow.

So at one moment in time I decided to go back to basics and chose a photodiode, which for its characterisctics is very similar to the sensor (that is also a photodiode, in the original circuit). The photodiode is a semiconductor that converts light into an electrical current, much like a solar panel. Turns out that using the photodiode as a lightmeter is not as simple as I thought (it never is actually).

My though was that making auto exposure was like having a built in light meter, in the sense of taking a measurement, determining the exposure value and then setting the shutter speed. And I guess there is nothing intrisically wrong with that. But there is another way. A sort of shortcut:

integration

Integration is what the engineers at Polaroid used. It is a simple idea, you take advantage of the battery-like characterisctics of a capacitor: you have the photodiode, which is like a small solar panel, that charges the capacitor -in real time- so when the capacitor is full the shot is correctly exposed:

Just imagine this crude comparison: the light is a liquid, so we have a funnel, that is the light sensor (captures the liquid, the light), it routes it through a pipe (which is equivalent to the resistor on original cameras) and then stores that liquid in a bucket (the capacitor).

(I apologize for the crappie video but that was the best I could do)

So when the bucket is full, the picture is correctly exposed and the shutter should be closed and picture expulsed.

That of course has many consecuences: it all depends on the size of bucket, smaller bucket needed for ISO640 film and larger for ISO125, that is exactly what the SX70 600 conversion does!

integration the openSX70 way: the magic number

The talented Dave Walker, one of the beta-testers, a electronics design engineer that nowadays works as an R&D manager, told me truth: my design was never going to work: in practice I “read” part of the spectrum, but the limits on the atmega328p analog-to-digital made it impossible to cover the whole range, say from EV6 to EV17 or something like that. Fortunately he knows A LOT and provided a few ideas, and much needed help.

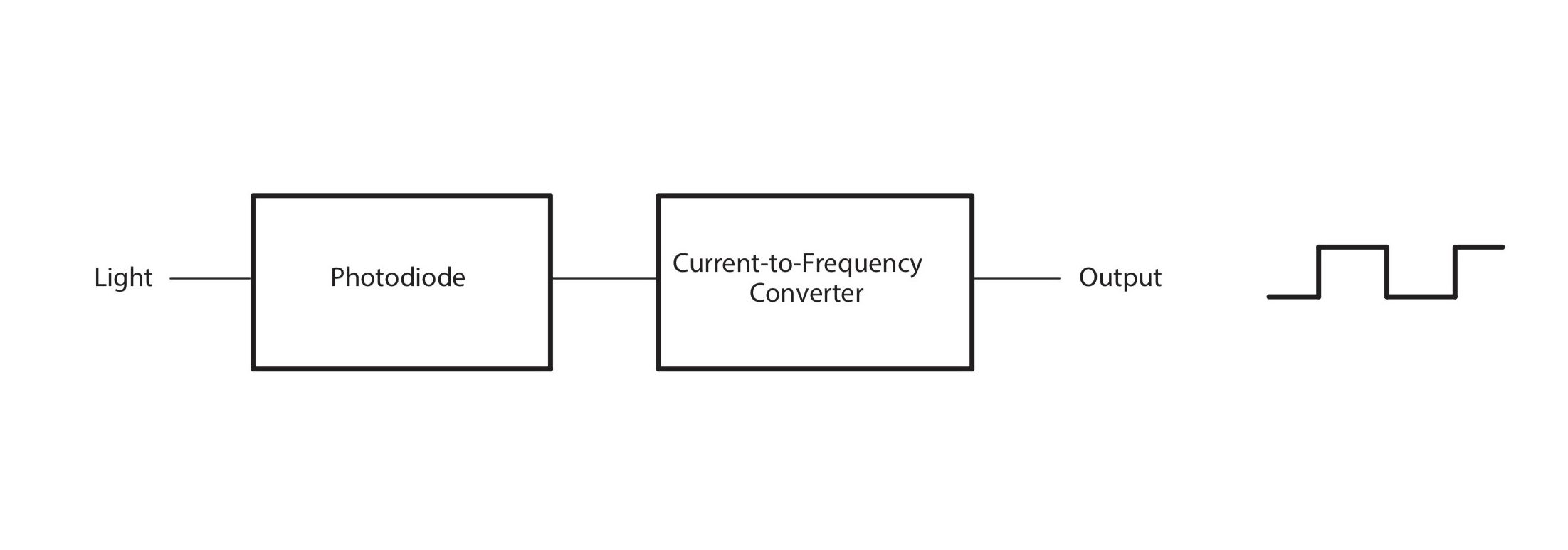

One of the ideas of Dave was to turn light into frequency: the more light, the faster the frequency.

Since frequency changes with light we just have to count… but wait! Let make a break to talk about….

interrupts

Ever since I started programming the Arduino I have tried to avoid interrupts: I knew that they were very important but also a bit complicated to set up. But the theory is simple: let’s pretend that you want to know if a switch is on or off, since Arduino is very fast you can keep on asking on every cycle are you on? Are you on?… every time.

That is called polling.

But there is another way: Interrupts. With these you just say to the microcontroller: “let me know when the switch is on” and go on with your business, you don’t have to worry, when the switch is on it will let you know and run whatever code of function that you want. It’s like magic (and yes, we are getting close to the magic number). Here is and explanation of interrupts vs polling

But of course interrupts can do much more like counting, so you can have it wake up when a switch has been turned on and of a certain number of times. But to do that you have to set a bunch of registers at the byte level, and of course all the information is in a data sheet longer than “War and Peace”: the mighty Atmega328P. Of course Dave’s help has been invaluable from the beginning of the idea. Bear with me.

So if we pick up on the integration idea, now think that instead of a bucket we have some sort of water mill, so when the funnel captures the light -a liquid in our example- it moves the water mill: what do we do then? We count the revolutions. And the question is: how many revolutions?

the magic number!

I want you to know that this one of few components proposed, the TSL235. It has a form factor that is different from what I thought it would be optimal. Other options are using the SFH2430 and a voltage to frequency chip lik the AD654 and more. What is nice about the TSL series of sensors is that it is an all in one solution, being theAD654 quite expensive and also quite big. The caveat for TSL is the dreaded NRND which means “Not Recommended for New Designs” and implies that the component might be near the end of life of the product cycle: maybe you do not want to use a component that might be scarce in the near future.

Rework

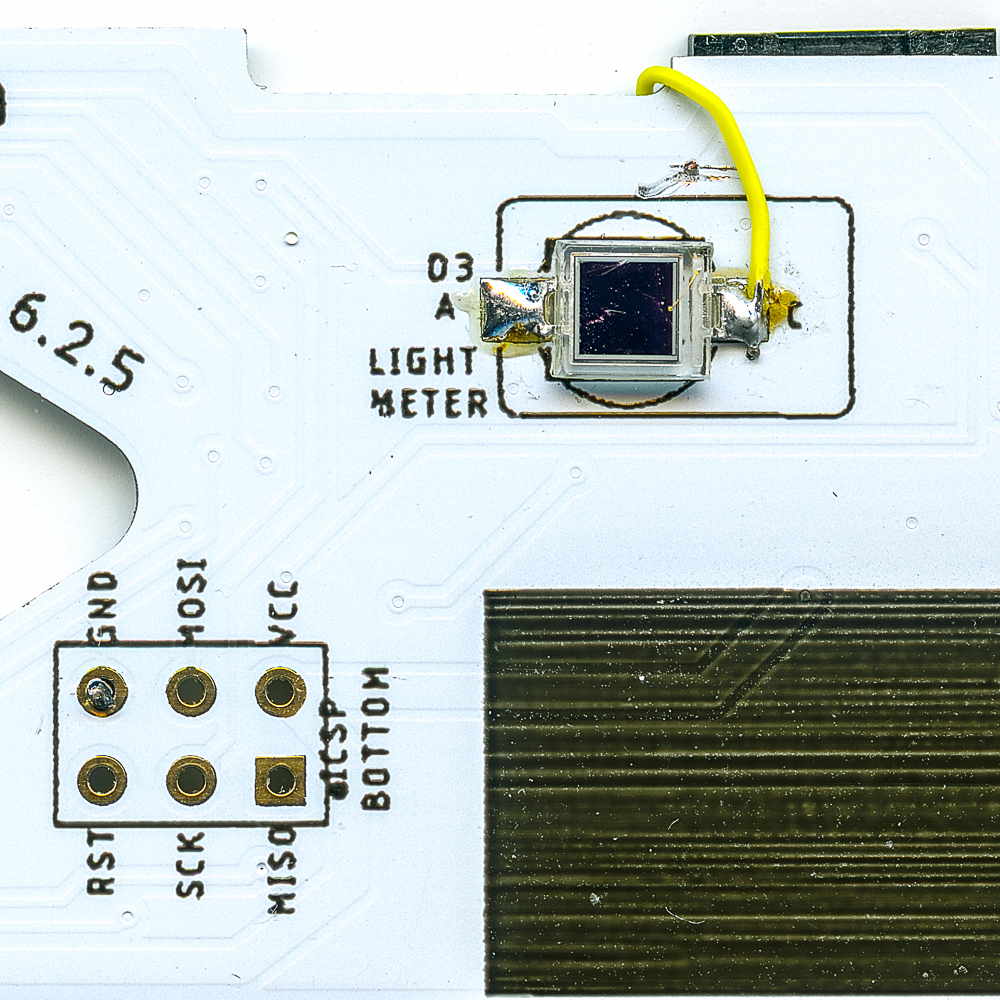

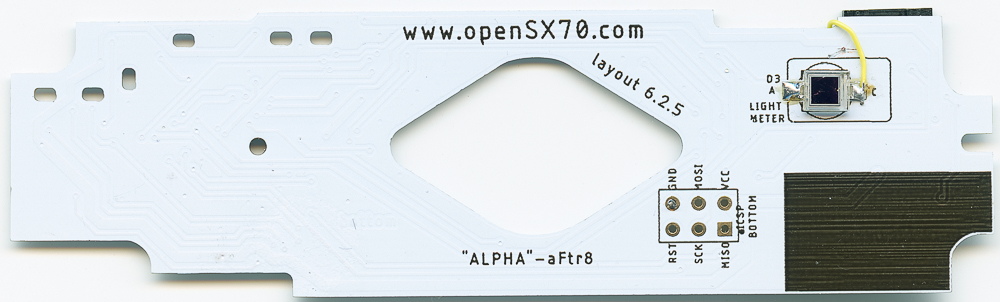

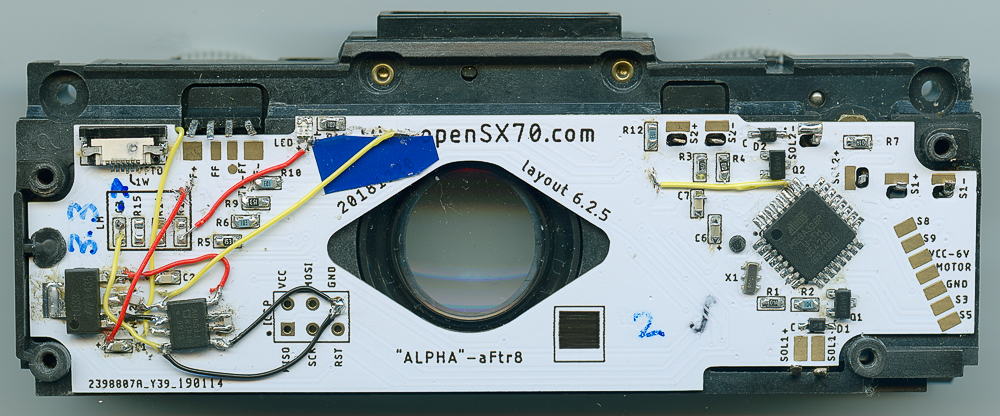

So to test the idea I have “reworked” the ALPHA PCBs with both the AD654 (no tests yet, it’s more complicating) and the TSL that seems to fit in the SX70 “window” for the sensor.

Lets say that I am not the best at this but I tried with very thin cables to redo part of the circuitry, here is the AD654:

And here is the TSL235:

This chip is similar in shape to what you usually find as a IR receiver.

Calibration

So how does one come up with the magic number?

Dave proposed to “sync somehow the shutter of an original SX70 with another sSX70 with the TSL235 (or whatever). That way if the “exposure donor” camera takes a proper exposure, we would have the magic number in the other camera.

One cool piece of code that I accomplished is that I can shoot in manual a know how many pulses the sensor has produced, that means what is the “number” for that picture.

So, instead of making test and stuff in a “dry dock” I just decided to put some film and try. Had to see it!

The test & results

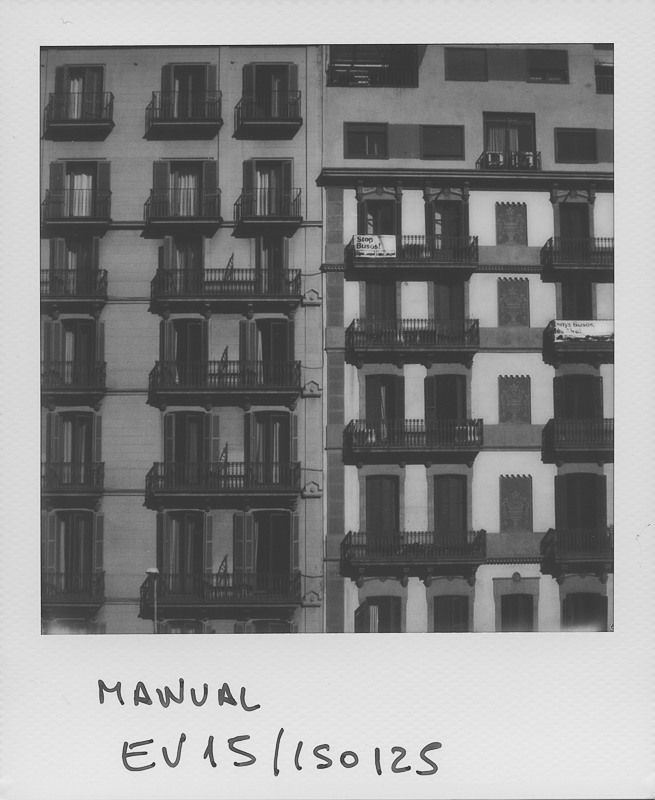

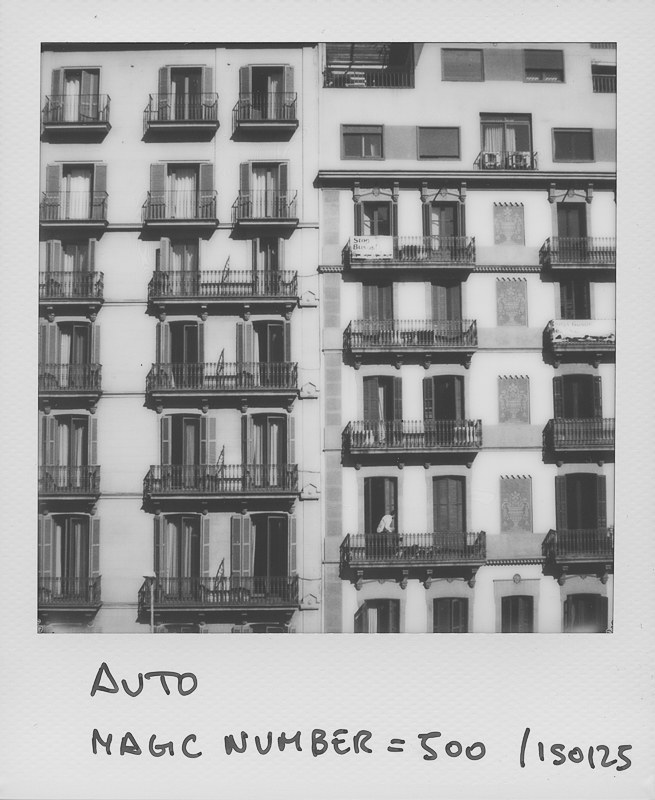

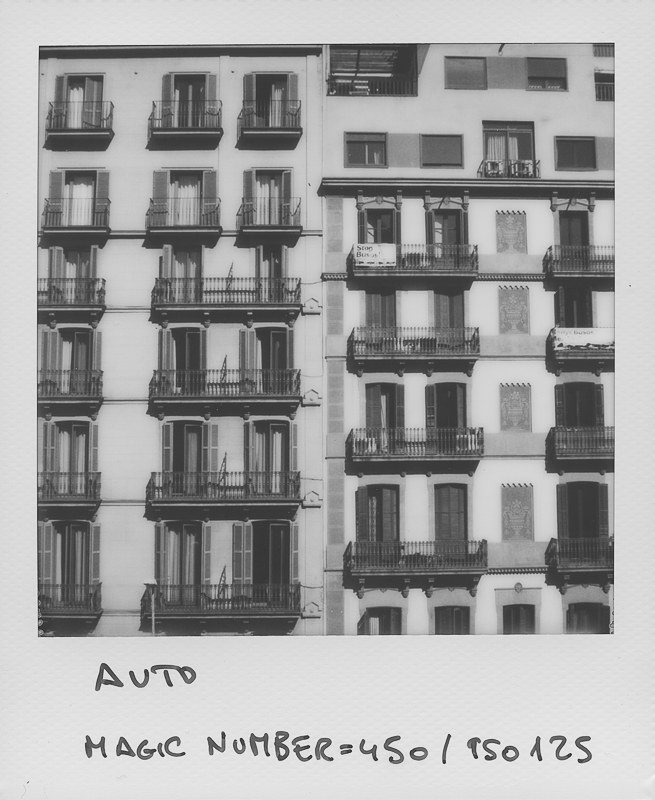

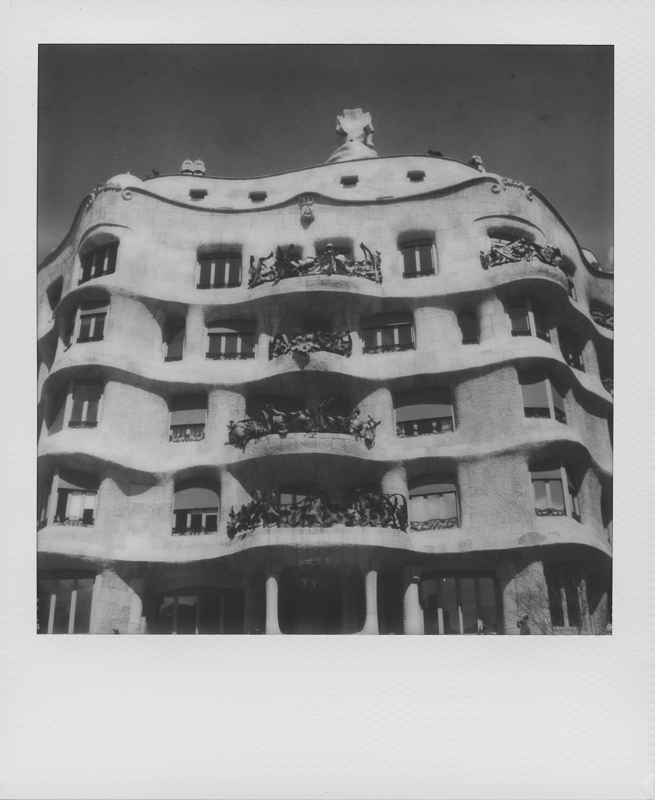

I chose fresh Polaroid Originals black and white film for the SX70. B&W because it develops fast, and SX70 type because I thought it might be easier to calibrate with the longer exposure times. I mean a higher magic number.

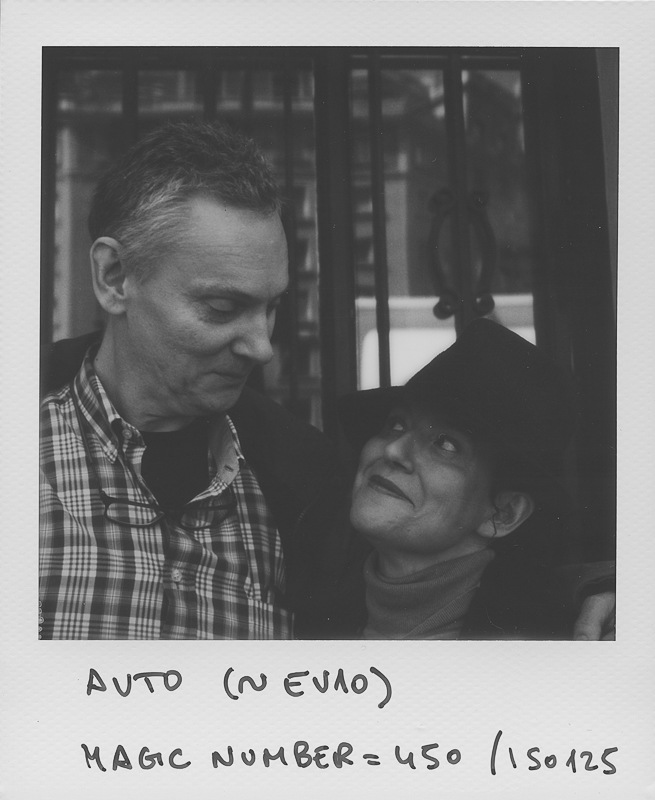

First I shot an manual at EV15. Just to see what the number said, then I started a value of 500 as the magic number, nothing scientific but the photo seemed a tad over so I went to 450. You can see here all eight shots that I took in the order I took them.

Comments